"Out in the street!"

The whole band crashes in with a doctored Bo Diddley beat and falsetto backing vocals as Daltrey growls to his woman. A brief talking blues moment is followed by Townshend flicking the pickup toggle switch to make his guitar stutter. then its back into the punchy groove. These lads have joined the party through the kitchen door and it's going off.

And that is pretty much the early Who. Except there's more.

Younger listeners might wonder at the presence of cover versions on the first outings of British Invasion outfits. There are reasons. First, these early platters were meant to represent the live band and no band ever began with a set list of originals. Second, covers were a way of identifying themselves to an audience who knew the numbers. Third, when you covered your heroes there was always the chance that you'd outdo them. Showbiz and hubris. On the latter, it was an act of defiance to follow their derivative opener with something by James Brown. Brown's original is one of his more subdued tracks. His vocal is mostly smooth and the track is piano led with shining backing vocals. The Who do all this but tighten the rhythm and thicken the texture with the same guitar attack as the first song. It's how we play it in Shepherds Bush, mate. It's the cheek of it that gets them through.

Then there's something that sounds like it crawled out of the drains. The Good's Gone begins with a jingling twelve string that starts a bright drone over the pulsing band. Daltrey comes in, mean as ever, complaining about the vaporising love in his relationships. He's joined by Townshend and John Entwistle on backing vocals. The track punches and drones for over four minutes (almost heretical even for an album track back then). Such an insistent return to the tonic note and a refusal to add too much as its long course plays out make it sound like psychedelia two years early. What Townshend is doing is trying to outdo Ray Davies whose powerful droning numbers like See My Friends and Tired of Waiting For You inspired any songwriter who heard them, leading to an heralded early eastern music influence into British rock. The harmonies repeating the title with their bright and smooth solemnity sound as much like a funeral dirge as a beat group love song. The Brits were changing rock music and it wasn't just The Beatles.

La-La-La Lies starts with a Motown rhythm on the piano, energetic tom toms from Keith Moon. Daltrey's vocal is almost sweet and the shoop shoop backing vocals could be from anywhere in the Vandellas' songbook. It's brief and enjoyable and feels like it's in there as a show of variety. Much too Much follows with a more natural British rock swagger with Daltrey recriminating from the shadows while the chorus turns the light on with Beach Boys choirs.

And then there's this. A pummelling assault of guitar and bass that are indistinguishable from each other and manic drumming. It's a song of pauses with instrumental responses.

People try to put us d-down. (Talkin' bout my generation)

Just because we get around. (Talkin' bout my generation)

The things they do look awful c-c-cold. (Talkin' bout my generation)

I hope I die before I get old. (Talkin' bout my generation)

It's all out salvo across the divide without a wink of cuteness. Nothing on this side has approached the hard density of this number. All members are driving with the rising to the seventh of the refrain, the hard crunching stops, Daltrey's intentional stutter that evoked a Mod searing with speed and Entwistle's gymnastic bass breaks. The home stretch where the backing vocals and the lead blend off balance under Townshend's powerchords leads to a key change that feels breathless and violent. Daltrey is outright screaming as the band sing the refrain in rapid fire underneath. It comes to a searing final chord and a final repeat of the title, emerging from the dust of the rubble. It's too big for the fade that would have routinely finished similar tracks from the time.

This song was a declaration of war that rang out well beyond the generation it claimed. It was 1977 before I heard it in full and it fitted perfectly in with the punk singles coming out of the U.K. at the time. Not a second of this song doesn't work. Even the stutter with its contested origins, sounds like someone too young and hyped to be polite blurting it all out because it has to come out. Like You Really Got Me, Satisfaction, The Beatles' version of Twist and Shout, this is song to play to anyone who doesn't understand what was so special about rock music.

If you heard this album on CD or an old C90 tape, the next song might have you puzzling as to why they followed one teen epic with another. The Kids Are Alright begins side two of the LP. Just as side one started with a Townshend signature guitar chord so does this except that it's very differently mooded. First, this is another twelve string rocker and the single guitar track dominates the same way that later Who songs would thunder with overdrive. This tone is clean and heavily compressed. It starts with a lone hard strum on an A sus4. This always struck me as a response to the brash bash at the start of A Hard Day's Night. That one would have bedroom guitarists puzzling for decades (it's an accumulation of all the band's instruments playing somethign different as well as a piano chord). That Townshend wanted to show he could do it, too, suits this song of sadness and anger perfectly.

After that chord the block harmonies come in acapella. "I don't mind" Daltrey takes over. As the band crashes through this constantly energetic rock song, his voice is as much a character performance as it is in My Generation. The two pair well as a kind of mini song cycle. But if My Generation was Clockwork Orange's Alex shouting at the world, this one is more like the original final chapter where the droogs are a few years older and mellowing out into normies. In The Kids it's the mod who needs to quit the scene. It's tough, though, he can't get married to his girl because they're both underage and her parents shut it down. The scene is getting samey and he wants to quit it for the rest of the world at least as far as he can go. Everything's old and sour now. The guys dance with his girl and he doesn't mind. It makes it easier, if anything, for him to quit and get out into the light.

The constant ringing guitar and stormy rhythm section provide a frenetic confusion for the situation. They sound like the best party band in history but the guy at the mic no longer feels it and hates that he has lost that. My favourite moment of this favourite of mine is the solo. After the third verse ends there's a kind of clearing of the floor. Townshend plays a single note. It feels small but solid. As a twelve string note it's doubled so it's shiny. This builds to a chord as the band swells around it, insisting until it's pumping, sharp and heavy. Then, a single big chord rings before a machine gun muted 16 round chord from the middle eight kicks everything back in and the final verse leads to a repeated harmony chorus with a slight variation in the higher register before ending with the opening sustain chord ringing below. If I have the time when I listen to this I always play the whole song again.

Please Please Please is another James Brown cover that does credible service to the original. It's a guitar led attack rather than the piano of Brown's version but it's performance, apart from Daltrey's impassioned screaming, is an impression rather than a conveyed message. It's Not True combines harmonies with a jaunty 2/4 beat and a strutting vocal from Daltrey. A series of increasingly absurdist lies that give it the sense of a first run of the far superior Substitute from the following year.

I'm a Man is a cover of Bo Diddley's assertive statement in talking blues which the Yardbirds had already fed amphetamines. The Who's version features the kind of dynamic arrangement with piano breaks, some electronic growling on the guitar as well as the Townshend stutter. But it's a different thing when Bo declares his stance in the world of chicken fried steaks and the much younger Londoner at the mic here. Daltrey sounds like the youngest Athur Daley Spiv in history or one of those people who wake up one day speaking Medieval French. The pretty twenty-one year old mod with the voice of the flasher from under the bridge cannot work. It probably did work live but here it sounds weird.

A Legal Matter is Townshend's only lead vocal. It's a kind of retake of the Stones' The Last Time, with a touch more country twang. His narrator is restless in his marriage and had served his wife up a divorce. While the sense of joke is high here, it sounds out of place already in an album with My Generation and The Kids Are Alright. The mood wouldn't be revisited until John Enwistle was asked to write the song for the molesting Uncle Ernie in Tommy.

The Ox is a whole band jam based on a pedestrian blues riff. Moon stars as the octopus drummer who is still lofty on purple hearts. A young Nicky Hopkins is heard giving the studio piano a workout. Some nice noise making on the guitar and amp combination from Townshend but this is one that I'll leave on only if I don't bother to press stop. It fades after a while. End.

Shel Talmy's production is different here. The thin and scratchy sounds of the early Kinks records has gone and is replaced by a much fuller sound and attention to the details of the blend. Townshend's compositional guitar playing is always exactly where it should be, whether he's sneaking around with automotive coughs, rapid stutters or proto power chording. Entwistle's bass is never shy nor allowed to fall below the mix into a general boom. Moon's drums are clear to the extent of detail of each part of the kit (well, under those circumstances, you shouldn't expect to hear a lot of kick drum) and the vocals, if at too many times, pitchy, come in where they need to. So, who did the learning? The Kinks albums kept sounding thin and The Who just kept growing. Ok, so this was the only Talmy production but Townshend's influence beyond it becomes clear.

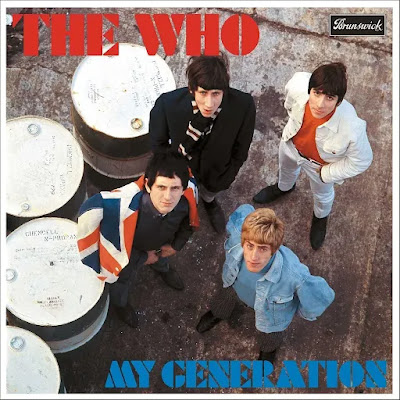

I still find those covers annoying because the originals aren't my kind of thing. But the best of this platter can make me crave repeat listening. The breadth of mood, from anger to humour, is impressive even in a scene where both qualities were abundant in postwar youth. The more I see these debuts in context of each other the richer I find the experience. If nothing else, this record served to slam the experience of a violent live sound into a vibrant and dynamic beast that could break its own bounds and keep running. The cover with its thick stencilled font in two colours features the band looking up from what might be the docks. None of them are smiling like The Beatles still did on their albums. Are they searching the sky or waiting for an answer to their challenge?

No comments:

Post a Comment