The primary note to make about the Yardbirds is that the band hosted three lead guitarists who went on to massive careers that left the band behind. The secondary note is the more interesting one about the split between a series of increasingly pioneering recordings and live sets anchored in electric blues. This one explains why their albums were so eclectic, ranging from fundamentalist 12 bar rave ups to mournful pop songs groaning with Gregorian choirs or wailing with electronic set pieces.

This tug o' war would end in tears. The first Yardbirds album was a live set of blistering blues that featured Eric Clapton evolving on his feet. Then, after a couple of white boy R&B singles they put out the extraordinary For Your Love, driven not by blues harp and a raunchy Gibson semi but a harpsichord. Clapton the purist got up, took his axe and left. Jeff Beck joined about two weeks later and ushered in an era of uneasy change with straining throwbacks but brilliant peaks. This is the album he starred in.

The real title is eponymous but, as with the double set called the Beatles but better known as the White Album, no one calls it that. The usual title given this LP comes from the drawing on its front cover. A big man with loping simian arms plods along, in one hand a pair of headphones with a torn cable and in the other a spool with tape trailing behind him. His expression sits somewhere between confusion and anxiety, the evident result of working with the band. Following the waves of the headphone cable, in florid lettering, is the name Roger the Engineer. The huge machine in the background is a kind of Heath Robinson rendering of a recording console whose mix of chimney stacks and computer reels would testify to the mystery of the recording process were it not for the long necked bird drawn on its side and the five eggs beneath it. It was drawn by guitarist Chris Dreja.

Lost Women starts with an R&B shuffle and a solid bass riff. Keith Relf starts in over this and with a delay worthy of his status to come Jeff Beck only comes in in the chorus firing machine pefect barre chords. It's pretty standard Yardbirds fare until the solo, the rave up section where Relf sets in with some hard and sorrowful notes on the harmonica and Beck discretely following beneath. Relf lets fly and just as we expect Beck to follow as Clapton would have he doesn't. Instead, he wanders around the studio, finding the good points for feedback, uses his guitar's volume knob so the long droning notes slide into the ears like serpents. He refuses to open fire as anyone who moved into the maestro's podium would. He smoulders and lurks, giving the blues shouter a sinister intensity. Eric Clapton would never have thought of that. That's the point.

We are plunged head first into the single with the full band chugging hard, shouting in time while Beck twiddles a riff high up on the fretboard that sounds like an Arabic reed instrument. Relf launches into a lyric about consumerism and hedonism which might as well be Rock Around the Clock until the verse grinds into another drone with Beck's string bends wail beneath the strain: "When will it end? When will it end?" Repeat! "Over under sideways down. Backwards forwards square and round..."

Beck had already earned his stripes at live gigs but also contributed real presence to the singles before this LP like Heart Full of Soul, Evil Hearted You with their sitar like riffs and grown up surf rock solos before the massive strange Shapes of Things with its droning guitar interpolations and a solo section that combined a million note noodle with distant howling but articulate feedback that was more like a montage from a horror movie than a rock song from its time. This is why if you hear a chronologically correct compilation album from the band the songs will start out with a few unremarkable electric blues workouts and then suddenly sound like proto-psychedelia. There were already progressive leanings within the band that made Clapton flee the scene. Jeff Beck moved in and drove that exploratory spirit and led the charge. His influence is all over this otherwise frustrating and inconsistent set.

That said, but also in proof of it, the next track is a straightforward blue by Beck which sounds like a throwback to the days before he joined. The Nazz Are Blue is an unremarkable 12-bar. Energetic, sure and stinging with Beck's fiery lead licks but seems to drag halfway through without recovery. Maybe Keith should have sung it.

I Can't Make Your Way is a jaunty pop singalong the like of which the band would head into in their final alienating period with pop producer Mickie Most. It's the kind of track that would turn up on re-releases of Who albums when John and Moonie had been larking about in the studio by themselves. Nice enough but ...

Rack My Mind is back to the tougher side with a bluesy rifferama. Beck adds dynamics to it by playing harmonics in the second verse instead of the expected riffing clanging in with a stabbing lead lick in the bars before the chorus and emitting tiny squeals and more harmonics in the final verse before soaring into a huge screaming solo as the song rushes to its close.

Farewell closes the old Side One with a gentle vamp on the piano. Keith comes in mellow and calm about his impressions of looking at the world as though for the first time. The others join in behind as a credible choir ah-ing and humming down the chords, building to a lush third verse with a delayed falsetto at the end of the lines. Finally it's just Keith and the piano saying goodbye to the future. Is this a suicide note? It must be history's most gorgeous one. I can never play this one just once.

If you hear this on CD or in digital form without the side divisions you will wonder what they were thinking. Hot House of Omagarashid starts with screams and a drum break over a wobble board. No lyrics but the band chanting yah yah yah. Somewhere between a Martin Denny exotica piece and watching an old Tarzan movie though a veil of lysergic acid this is the most infectiously fun track on the album.

Jeff's Boogie seems to put the lie to any claim I made about Beck's yen for musical adventure as it's a plodding and uninspired 12-bar instrumental begins big and ends eventually. Listen for the guitar tone, maybe.

He's Always There draws into intrigue straight away as a downward darting riff and droning harmonies tense us up. It's like a weird minor key version of Shout. Across the room the narrator locks eyes with a babe and it means something but the guy, the man, the ape, the protector, the jailer, the husband, is always with her. The chorus breaks out in a looser time and a progression that sounds like The Who in their darker moments and ends down in whisperville with the title line as some tight latin percussion scrapes away. After two of those the whisper strains on as a kind of secretive, obssessive call and response. Everyone's been here.

Turn Into Earth slows its brisk three time down with a tolling piano chord progression. Minor rubs against major in the same modal mash that made Still I'm Sad so extraordinary. A lighter Gregorian wordless chanting starts and Relf's lead vocal seems to peel off from it. If Farewell was a suicide note in disguise Turn Into Earth is a whole manifesto. I can't hear Joy Division covering it but boy is the mood on their street. It's most likely Relf writing with the mood of the music. Still, the lyric is neat and forceful, leaving no escape route from "the darkness of my day." This, it should be remembered was the year of Paint it Black and Eleanor Rigby hitting the charts. But the knelling surrender in this one seems to outdo both as it waltzes on past the final statement, a kind of anti-light in all that paisley.

Urgent ride cymbals are joined by amp-distorted bass. A guitar chimes in and then Jeff comes in with slower barre chords gleaming with light distortion. Keith yells a 7th down to fifth tune (think Last Train to Clarksville, very common trope). Beck plays with the vamping rhythm guitar with bends, harmonics, amp tremolo, spilling colours all over the verses and noodles in the pentatonic in the choruses. He's slow to come into his solo and when he does it's a combination of all of those things, some flash, some mood lighting and feedback all into the fadeout. Exiting with drama that goes beyond the stage.

The final track explodes with operatics as Relf in his nastiest snarl tells us of the root of all evil in Ever Since the World Began as a piano sits in for a tubular bell and the choir sings the word money in fifths like a hellbound chorus line. This weirdly gives way to a guitar shuffle in a major key. Big bass underneath and more amp tremolo. Keith keeps on theme but this time firmly in swinging London as the goblin choir behind him changes from their scarlet drags to discotheque paisley, clicking their fingers and chirping, "ya don't need money". Relf delivers his last couplet ending with: "you sold your soul the answer's no." And everything stops. Breaks no, no screech. Bam. End. Huh?

Whether more tracks were planned or that was meant to lead on to another track with the sudden ending giving way to something more dramatic is unknown to me but it's a final statement that goes rapidly from a bang to a whimper with nothing to follow. One of the strangest endings of any conventional rock album I've ever heard. The movie has that one last scene that completely twists everything you saw, lasts for a few seconds of one shot and the credits roll against a stark black field.

I don't know that I should still be surprised by this, given that I've known this album for decades now (I bought the early 80s reissue) and have always considered it strange the way that rushed creative work always does. The new hotshot guitar slinger comes in for the big production, adds some flash here and there but mostly keeps to the atmosphere, drawing it from some unlikely shadows and always impressing with his restraint in the application. The band as a whole present their first wholly original set and it's an uneasy pull between their live reputation as blues shouters and the electro-pioneers they were on the pop charts. Both approaches have mediocre produce along with the brilliance and we end up with this uneasy jumble.

It's important to remember that not everyone in the great British rock 'splosion o' the 60s wasn't detonated all at once nor by teams as unified as The Beatles or the Rolling Stones. Listen to the early Who albums to hear similar awkward shoehorning of live and studio identities. While The Who and The Kinks ironed this problem out on record The Yardbirds weren't so well served. Unstable from the word go, the line-up seemed publicly dependent on the star guitarist and, while there was clearly some songwriting talent to go with the wonderboys' sonic inspiration, so much of it was left there. Two paint-by-numbers 12 bar work outs that drag everything down so the new axeman can be featured completely belie all the really intriguing stuff he was putting in on the rest of the tracks he was on (Farewell is the only one without any guitar). And for all of Beck's hotshot flash his major contributions to the Yardbirds' greatness were the magnetic sonics he used to transform their pop singles rather than take any earnest opportunity for an extended workout on a long player.

After this album Beck's friend, the one who'd passed up earlier and recommended Jeff, Jimmy Page joined and briefly added his own brilliance to Becks live and in a few singles (can see the lineup in the movie Blow Up). Beck got sick and left and Jimmy took over just in time for Mickey Most to try and turn them into Herman's Hermits as they crumbled in his hands, leaving a few minutes of psychedelia here, some proto-heavy metal there, a lot of unconvincing pop and a lot of mess. A year after this the band had morphed, losing a face here and gaining another there until they had to admit they weren't The Yardbirds but Led Zeppelin. And from that time there were no more tigers in the village.

But here we have a strange thing. A set of massive potential recorded well for a change, it cannot lift its slighter moments to the heights around them and as a result they come off worse than filler. Islands of greatness in an ocean of gormless failures. Harsh? Maybe, but this is what happens when a band puts all its eggs into a star player and still tries to chase up those good ideas that he'd normally not be part of. Curiously, Beck did take part in the good ideas, bringing plenty of his own. It's just that when they rendered unto their old identity it sounded forced and fake. This is a shame as while that strip of outstanding songs that hint at sounds beyond their time in the compilations seems betrayed at first listen to a set that was intended to sit as a collection but can't. The ideas are there, it's just takes a few listens. The trick is getting beyond the first, or even through it. But do it.

Listening notes: I used to own a deep dish reissue of the stereo mix from the 80s but for this referred to a more recent CD remaster, namely the mono mix on the 2 disc Repertoire set (the pic I used in this post is not quite the cover art but it mostly is).

Monday, October 31, 2016

Wednesday, October 26, 2016

1996 at 20: Ten Albums from the First Decade on the Web

The 1990s gave me a new relief: I no longer had to pretend to like any contemporary rock music. Everything guitar based that I would hear just sounded like old stuff. Now and then there'd be a Kurt Cobain who had real things to say and said them powerfully but mostly it was copyists of him or the whole industry of copyists in the U.K. led by the forgettable Blur and Oasis. Rock music sounded like a 24 hour tribute show and made itself easy to abandon.

One sub industry I did take to was trip hop, the morphed distillation of the clever part of rap stretched into danceable grooves or stretched down to rainy afternoon cinema by the likes of Tricky and Portishead. Also, having initially dismissed it I grew to understand techno and EDM and, if I didn't love that, at least preferred the approach. Both of these forms of electronica spawned masses of copyists, true, but the sound had more substance and freshness that the big wash of clones at least made for a luxuriantly textured carpet.

Apart from exchanging home burned CDs with friends I discovered the new stuff through looking it up on Allmusic or UBL and moving laterally from any of those points. Later in the 90s this also involved going on peer-to-peer and getting anything you wanted. As there was less of a sense of time sensitivity (put age in there, as well) the searches went in all directions. 1996 thus became the most eclectic of all the decades I'll be looking at. Vide!

Beck - Odelay

More sophisticated and mature than his breakthrough Mellow Gold, Odelay remains an enjoyable listen by a randomist trickster with serious composition skill. Mellow Gold remains stronger for the force its rawness lets through. Beck changed direction almost immediately after Odelay, fitting comfortably into a singer songwriter role by which he found a new audience and left his first behind. I was among the latter. Odelay was fun but Mellow Gold was funner. Still, the mash em up and glue em down method worked again and until you heard a CEO ruin it by using the term lo-fi in an address it was pretty good fun.

Lamb - Debut

Trip hop was entrenched by the late 90s. You could take it anywhere and heard it everywhere. Techno doofed the festivals and clothes shops, happily minding its own business. The difficult one was jungle or drum and bass as, while everyone admired it, no one got what it was meant to do. This duo from Manchester had the idea of programming all the severity you could eat in the rhythm but make it serve real songwriting. The fractured samples, multi-layered choruses and strong jazzy lead vocals showed us we could connect with the alien genre the same way we did with Tricky or Portishead. Of course, once established as the underdarlings of the boutique and cafe, Lamb were unpersonned by the gatekeepers of jungle and forced into the wilderness of the mainstream where they had hits 'n' stuff. The whole album is still strong, resists the saturation problem with most pop by keeping the hooks low profile. And then there's Gorecki, a long crescendo of celebration of twig and branch beats, sampled symphony (from the 3rd symphony of the title composer's works) and a prayer-like declaration of love and wonderment calling out from the bliss. Still fresh.

Morcheeba - Who Can You Trust?

At the cooler, wounded end of the trip hop street was this London trio of two brothers and a lass at the mic. A rich mix of electronics, bottleneck guitar and smoky vocals over break beats is far less impeded by time than many of the cash-ins that followed Portishead and Massive Attack out of Bristol. The following year's Big Calm is the easier gateway with a flashier pop sensibility and hooks but this afterparty chill can still fill the exiting thrill on an early Sunday morning.

Mazzy Star - Among My Swan

The double act from Rainy Street emerged from three years of touring and radio silence with a set that followed the formula of the two previous albums, big spacey opening track, a fragile acoustic number, a noisy whisper fest, and a handful of aching near country near psychedelia textures. This sounds like I'm about to dismiss it but Among My Swan is a fine album. It's a little sludgier in texture than either of the first two but this just feels further along the road. Less pops out but there are real aches in Still Cold, Rhymes of an Hour. Still works a treat, in fact, the whole thing.

Swans - Soundtracks for the Blind

From unsettling childish prattling to real FBI stakeout recordings to terrifying confessions and deceptively sweet techno ballads Swans' exit after one and half decades of local blitzkrieging gathered all its experience and ordered it like a series of William Cornell boxes. Not one of them was pure but mixed with the traits and even material from other phases. Tapeloops, massive one-chord storms, and more and more still create a rich and complex texture that can be visited for tens of minutes but not cherry picked. The whole thing in one sitting is too much. You're getting everything they were capable of, crammed into every last nook of sound. This was their last will and testament. Following the live album with the joke title (Swans are Dead) there would be various solo efforts until Gira's resurrection of the name with mostly new personnel this decade but no Swans. Jarboe ventured further and further out on her own branch, getting darker and stranger until the dark and the strange was she herself, free of the evisceration of the band she'd struggled and shone in. This massive landscape of pain and analgesia had to stand. So it does.

Dead Can Dance - Spiritchaser

The plainest and least bombastic of all the DCD albums, Spiritchaser comes and goes pleasantly and doesn't outstay its welcome. I like the bombastic stuff better. Then again, they were is a strange position in the mid-90s as the strain called world music emerged and spread o'er the globe. At one end of its spectrum it was innovative and at the other it sounded like updated Martin Denny muzak (which I like, btw, just sayin'). Dead Can Dance could try to protest that they'd clued into this a decade earlier and with much greater originality. So, they couldn't win. Make it bigger and brasher or slim down for a near unplugged approach. They tried the latter. Well,

Tricky - Pre Millennium Tension

I've already written a main post about this one and explained why I can only listen to picks rather than the whole thing. Those, though, are still fresh.

Tricky - Nearly God

Hissing, whispering and crying with gooey electronics, this anthology of collaborations between Tricky and various pop vocalists variously wows and numbs. I don't mind it now and then but if I realised what I'm listening to I'll usually last only a few tracks before going somewhere else.

Beth Orton - Central Reservation

The decade of articulate soloists brought forth a healthy spirit of experimentation. While they might have started out with just a book of biro-ed lyrics and an acoustic guitar in their bedrooms new folkies like Beth Orton were happy to mix it up with breakbeats and electronics. I first heard Orton's hit lead-off for this album, She Cries Your Name, as a scratchy realaudio ten second sample. That was enough to sell the album to me. I don't love it now but can still hear it if it's sourced for a VOD show.

The Handsome Family - Milk and Scissors

There are some real standouts on this second album like Winnebago Skeletons and the dizzy 3/4 nihilism of Drunk by Noon but it doesn't hold together as a set as it feels like they haven't decided whether to be indy but a little bit country or all out country. They found a clear path by the next one, the extraordinary Through the Trees, and never looked back. It demonstrated the difference between the country leanings of Winnebago and the indy cuteness of Three Legged Dog (given to the main singer's brother to sing). I cherry pick tracks from this one. Everything after it varied from greatness to a notch above just ok.

Sneaker Pimps - Becoming X

I worked in Bourke St and my stroll home would often involve a step into Gaslight Records to see what had come in. This had grown sparser and I was really just down to flipping through the soundtracks to see if anything like Near Dark or Suspiria had come in. One afternoon I found myself to be the only customer. I was about to make the usual flip through the movies section and leave but started taking notice of the music that the lone guy behind the counter had put on. It had a lot of the mood and atmosphere of the best of trip hop but there was a lot more energy in the songs. A magnetic female vocal rode the waves of electronica and a rock sensibility that worked because it wasn't centre stage but just another texture. And then came the final track, a rattling and pulsing rendition of the seduction song from The Wicker Man. Man. It was something new that I liked. I asked the guy what it was and the name was so odd that I had to have him repeat it, slowly. Before I could get to that part of the shop he volunteered that the one he was playing was the last copy. I went home with a kind of levitation autopilot and played the entire thing again. Everything fit, song after song, drama, cinema, melody and a glorious pallet of sounds and textures. It rocked, it boogied, it slunk and skulked. It went from Friday night to Sunday morning to the 3 a.m. of a day so confusing it could be anywhere in the week. I still play it.

...

It was at the end of this year that I went to the final of a friend of mine's Xmas afterparties. He lived in the city and held these superb gatherings for everyone who had to endure family xmas duties or those who had more pleasantly gone to orphans' dos. His afterdos went from breezy in the late afternoon to stompin' in the early morn. At one stage while it was on the turn from one state to another he asked allowed what music he should go to. I suggested Portishead and he scoffed and said: "Nah we need something newer than that." Then he went and put on the most recent Oasis album. Dummy was only two years old and still sounds current. Morning Glory was also two years old but still sounds like it was released in 1983. It was just another point of relief. I might not have been cured of rock music but when mediocrity like Oasis was being hailed as its saviour it was time to leave the room. I went and had a conversation that sounded louder than the music.

One sub industry I did take to was trip hop, the morphed distillation of the clever part of rap stretched into danceable grooves or stretched down to rainy afternoon cinema by the likes of Tricky and Portishead. Also, having initially dismissed it I grew to understand techno and EDM and, if I didn't love that, at least preferred the approach. Both of these forms of electronica spawned masses of copyists, true, but the sound had more substance and freshness that the big wash of clones at least made for a luxuriantly textured carpet.

Apart from exchanging home burned CDs with friends I discovered the new stuff through looking it up on Allmusic or UBL and moving laterally from any of those points. Later in the 90s this also involved going on peer-to-peer and getting anything you wanted. As there was less of a sense of time sensitivity (put age in there, as well) the searches went in all directions. 1996 thus became the most eclectic of all the decades I'll be looking at. Vide!

Beck - Odelay

More sophisticated and mature than his breakthrough Mellow Gold, Odelay remains an enjoyable listen by a randomist trickster with serious composition skill. Mellow Gold remains stronger for the force its rawness lets through. Beck changed direction almost immediately after Odelay, fitting comfortably into a singer songwriter role by which he found a new audience and left his first behind. I was among the latter. Odelay was fun but Mellow Gold was funner. Still, the mash em up and glue em down method worked again and until you heard a CEO ruin it by using the term lo-fi in an address it was pretty good fun.

Lamb - Debut

Trip hop was entrenched by the late 90s. You could take it anywhere and heard it everywhere. Techno doofed the festivals and clothes shops, happily minding its own business. The difficult one was jungle or drum and bass as, while everyone admired it, no one got what it was meant to do. This duo from Manchester had the idea of programming all the severity you could eat in the rhythm but make it serve real songwriting. The fractured samples, multi-layered choruses and strong jazzy lead vocals showed us we could connect with the alien genre the same way we did with Tricky or Portishead. Of course, once established as the underdarlings of the boutique and cafe, Lamb were unpersonned by the gatekeepers of jungle and forced into the wilderness of the mainstream where they had hits 'n' stuff. The whole album is still strong, resists the saturation problem with most pop by keeping the hooks low profile. And then there's Gorecki, a long crescendo of celebration of twig and branch beats, sampled symphony (from the 3rd symphony of the title composer's works) and a prayer-like declaration of love and wonderment calling out from the bliss. Still fresh.

Morcheeba - Who Can You Trust?

At the cooler, wounded end of the trip hop street was this London trio of two brothers and a lass at the mic. A rich mix of electronics, bottleneck guitar and smoky vocals over break beats is far less impeded by time than many of the cash-ins that followed Portishead and Massive Attack out of Bristol. The following year's Big Calm is the easier gateway with a flashier pop sensibility and hooks but this afterparty chill can still fill the exiting thrill on an early Sunday morning.

Mazzy Star - Among My Swan

The double act from Rainy Street emerged from three years of touring and radio silence with a set that followed the formula of the two previous albums, big spacey opening track, a fragile acoustic number, a noisy whisper fest, and a handful of aching near country near psychedelia textures. This sounds like I'm about to dismiss it but Among My Swan is a fine album. It's a little sludgier in texture than either of the first two but this just feels further along the road. Less pops out but there are real aches in Still Cold, Rhymes of an Hour. Still works a treat, in fact, the whole thing.

Swans - Soundtracks for the Blind

From unsettling childish prattling to real FBI stakeout recordings to terrifying confessions and deceptively sweet techno ballads Swans' exit after one and half decades of local blitzkrieging gathered all its experience and ordered it like a series of William Cornell boxes. Not one of them was pure but mixed with the traits and even material from other phases. Tapeloops, massive one-chord storms, and more and more still create a rich and complex texture that can be visited for tens of minutes but not cherry picked. The whole thing in one sitting is too much. You're getting everything they were capable of, crammed into every last nook of sound. This was their last will and testament. Following the live album with the joke title (Swans are Dead) there would be various solo efforts until Gira's resurrection of the name with mostly new personnel this decade but no Swans. Jarboe ventured further and further out on her own branch, getting darker and stranger until the dark and the strange was she herself, free of the evisceration of the band she'd struggled and shone in. This massive landscape of pain and analgesia had to stand. So it does.

Dead Can Dance - Spiritchaser

The plainest and least bombastic of all the DCD albums, Spiritchaser comes and goes pleasantly and doesn't outstay its welcome. I like the bombastic stuff better. Then again, they were is a strange position in the mid-90s as the strain called world music emerged and spread o'er the globe. At one end of its spectrum it was innovative and at the other it sounded like updated Martin Denny muzak (which I like, btw, just sayin'). Dead Can Dance could try to protest that they'd clued into this a decade earlier and with much greater originality. So, they couldn't win. Make it bigger and brasher or slim down for a near unplugged approach. They tried the latter. Well,

Tricky - Pre Millennium Tension

I've already written a main post about this one and explained why I can only listen to picks rather than the whole thing. Those, though, are still fresh.

Tricky - Nearly God

Hissing, whispering and crying with gooey electronics, this anthology of collaborations between Tricky and various pop vocalists variously wows and numbs. I don't mind it now and then but if I realised what I'm listening to I'll usually last only a few tracks before going somewhere else.

Beth Orton - Central Reservation

The decade of articulate soloists brought forth a healthy spirit of experimentation. While they might have started out with just a book of biro-ed lyrics and an acoustic guitar in their bedrooms new folkies like Beth Orton were happy to mix it up with breakbeats and electronics. I first heard Orton's hit lead-off for this album, She Cries Your Name, as a scratchy realaudio ten second sample. That was enough to sell the album to me. I don't love it now but can still hear it if it's sourced for a VOD show.

The Handsome Family - Milk and Scissors

There are some real standouts on this second album like Winnebago Skeletons and the dizzy 3/4 nihilism of Drunk by Noon but it doesn't hold together as a set as it feels like they haven't decided whether to be indy but a little bit country or all out country. They found a clear path by the next one, the extraordinary Through the Trees, and never looked back. It demonstrated the difference between the country leanings of Winnebago and the indy cuteness of Three Legged Dog (given to the main singer's brother to sing). I cherry pick tracks from this one. Everything after it varied from greatness to a notch above just ok.

Sneaker Pimps - Becoming X

I worked in Bourke St and my stroll home would often involve a step into Gaslight Records to see what had come in. This had grown sparser and I was really just down to flipping through the soundtracks to see if anything like Near Dark or Suspiria had come in. One afternoon I found myself to be the only customer. I was about to make the usual flip through the movies section and leave but started taking notice of the music that the lone guy behind the counter had put on. It had a lot of the mood and atmosphere of the best of trip hop but there was a lot more energy in the songs. A magnetic female vocal rode the waves of electronica and a rock sensibility that worked because it wasn't centre stage but just another texture. And then came the final track, a rattling and pulsing rendition of the seduction song from The Wicker Man. Man. It was something new that I liked. I asked the guy what it was and the name was so odd that I had to have him repeat it, slowly. Before I could get to that part of the shop he volunteered that the one he was playing was the last copy. I went home with a kind of levitation autopilot and played the entire thing again. Everything fit, song after song, drama, cinema, melody and a glorious pallet of sounds and textures. It rocked, it boogied, it slunk and skulked. It went from Friday night to Sunday morning to the 3 a.m. of a day so confusing it could be anywhere in the week. I still play it.

...

It was at the end of this year that I went to the final of a friend of mine's Xmas afterparties. He lived in the city and held these superb gatherings for everyone who had to endure family xmas duties or those who had more pleasantly gone to orphans' dos. His afterdos went from breezy in the late afternoon to stompin' in the early morn. At one stage while it was on the turn from one state to another he asked allowed what music he should go to. I suggested Portishead and he scoffed and said: "Nah we need something newer than that." Then he went and put on the most recent Oasis album. Dummy was only two years old and still sounds current. Morning Glory was also two years old but still sounds like it was released in 1983. It was just another point of relief. I might not have been cured of rock music but when mediocrity like Oasis was being hailed as its saviour it was time to leave the room. I went and had a conversation that sounded louder than the music.

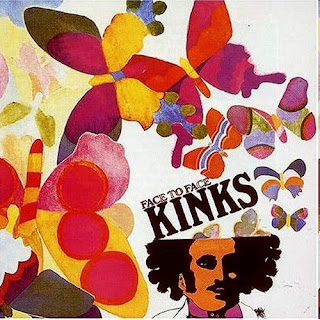

1966 at 50: The Kinks' Face to Face

Made from industrial strength disaster, Face to Face was the Kinks' strongest set to date. The band ended their 1965 tour of the US in disgrace with a ban that would keep them from maximised international success for years. The reason for the ban is obscure to this day but involved mismanagement and the constant internal violence that seemed to plague the band from the moment of their success. Songwriter in chief, Ray Davies, suffered a nervous breakdown in the months leading up to this set. He was entertaining the idea of doing a Brian Wilson and sending out a substitute singer to better handle the menacing confusion of adoration and hostility that playing to audiences meant. He just wanted to write his songs and play them with his mates. Well, it's more involved than that but that is in effect where he found himself at the beginning of 1966. And that is where he wrote, sang, played and oversaw the album Face to Face.

With the British invasion the notion of rock groups who didn't also write their own songs was cast into antiquity. The Kinks, like the Beatles, Stones and everyone else, recorded their first LPs as their stage shows plus a few originals if you were lucky. Albums were singles extenders, higher priced platters of more of that sound in which the glamour shot cover art was about equally important as the tones on the grooves, product for purchase. The Beatles upped the ante in '64 when the Hard Day's Night album not only pushed their songwriting further but was composed entirely of Lennon McCartney originals. And then at the end of '65 produced Rubber Soul which threw down a gauntlet by not only being good but cohesive. It felt like a whole package, not just a group of songs. Face to Face is the first Kinks album of wholly original material. But it's more than that. While the R&B influenced rockers are still plentiful there's a lot more here.

We start off with an old telephone ring. A posh voice answers: "Yes, hellair whoo is thet speeeking pleeeese?" And BAM Party Line bursts forth. It's a Dave Davies number with a big shrill lisping yell and clanging guitars. It's about confusion and the words swing between trying to connect to someone else out there and the party lines that form during elections. Whether cobbled together or not it's a pretty indicative statement for the rest of the album in which brother Ray is going to lay his pysche bare and hone all those lashing attacks on the society around him. Confusion and anger you can dance to. Odd thing: the main verse melody of this song is identical to the song Connection on the Rolling Stones' Between the Buttons album from the year later. Don't recall anyone else pointing that out (though it might have happened at the time).

Rosie Won't You Please Come Home? begins with a descending progression through a minor key. Ray comes in with a plaintive high voiced melody, pleading for his sister to come back. This isn't a fictional character like Eleanor Rigby. Rosie was really his sister. Her departure for Australia in '64 had a profound effect on him. When he learned of it he ran to the seaside and screamed. Here he uses that to dive into the well of longing. She's not dead, just a long way away and no longer the reassuring hand on the shoulder or tales of fun in the West End or lessons in working the world. The rest of the family is there but he still feels alone with no one there to get what he is. The words are plain, often bathetically funny. She's never coming back because once things change they will never revert because when they do they feel fake and tokenistic. This is atypical for a rock band to come out with so early in an album but Ray was hinting at all sorts of things in those oddball numbers he'd throw in before like The World Keeps Going Round or See My Friends, strange melancholic daydreams. Even singles like Tired of Waiting have a heavy middle. Amid all the rave-ups like Till the End of the Day there was Ray, staring out the window lost in a rainy day.

Dandy starts with a chugging acoustic guitar and picks up with a Kinks trademark swagger. The young Lothario of the title runs around Swinging London like a stray tom cat on the make, hearing the stern warnings of friends and parents with equal disregard as he slinks around the windows and the backdoors winning and breaking hearts. He's one of the new youth of the 60s, uncrushed by national service and earning enough to keep his wild oats sowing as constantly as possible. He is fun and he is damage but, guess what, he's alright. I like the cover of this by Herman's Hermits a lot, it's fuller in production and the zingy middle eight has a real snarl to it. But it's also short of the acting that Davies gives it, he observes from only a few years' experience over his subject but it's enough to describe him perfectly and give a yell of support that mixes a supporting cheer with a croak of regret. His own days of dandyism are leaving and, like everyone approaching their mid twenties, thinks that his fifties might as well start in a few months.

A gorgeous acoustic guitar figure opens Too Much on my Mind. A loping bass below it swings up an octave (skillfully avoiding fret noise) and Ray comes in, taking us through what it feels like to have too many thoughts. His delivery is aching and reminds us of how strongly emotive his vocals are. Never is this more poignant than when he's on intimate ground. The middle eight of Set Me Free still sends shivers when I hear it breaking between self-annihilation and menace and it's as soft and quiet as the worst kind of resolve. Here, he sounds like he hasn't slept for days, forging out only the statements he knows to be true and none of them are pleasant. The song could easily be a wistful love gone wrong lament and no one would think the worse. But Davies uses this setting to talk about his breakdown. He isn't Syd Barrett, he doesn't go in and scream or record seventy takes of one part, he arranges his song to the last bar, oversees the performance and takes the mic in character. He's not in the pit when he does this but remembers it perfectly and the symptom he chooses is one that everyone who listens will know: insomnia. The strength it takes to front up to a microphone and play it vulnerable impresses here. Not melodramatic just drained, defeated, behind him the lilt of the beauty he knows he has created and which abandons him at his worst. But as the artist he is he waits and gets to work when he is once again able.

A bright harpsichord arpeggio bursts out and Ray's wry vocal comes in with the band telling us about one of the most important and unsung aspects of rock recording in the 60s, session players. The one in this song thinks very highly of himself, letting everyone know why they should think highly of him for what is really just doing the same job as anyone else minus the inspiration or feeling. He plays his notes and goes to the next job. Davies' taunting calypso inspired tune is thought to be a dig at Nicky Hopkins but I don't buy that. Not only is Hopkins playing on the track (that's his harpsichord, sounding pretty intentionally perfect and emotionally flat) but graced plenty of Kinks records thereafter as well as all but being the keys man on British records from the mid '60s to his death in the '90s, celebrated for both high skill, inventiveness as well as an egoless ability to fold in with the music as it was. Ray hinted that this song began by being about Hopkins and more recently Jimmy Page was thought to be the target (due to a fan-authored contraversy about who played the solos on early Kinks hits). But all this really has to be about is a session man, strolling from studio to concert hall, lending his grade five piano skills to advertising jingles and walloping rockers as London swang around him inventing its own fresh fun.

A thunderclap and ominous chord grinds on acoustic guitar and piano. As Ray comes in with a voice choking with dark awe as the summer day before him removes its mask to reveal the darkness that is always there underneath. Add a little rainwater and the hope sags, predators natural and supernatural emerge from the shadows and strike. If Too Much on My Mind was a calm recounting of an emotional extreme there is little in the way between the observer and his fear this time. Dave's guitar plays simple descents, plugged into the tremolo of his amp so that even the weaponry of rock music trembles with nerves. "Everybody felt the rain." Sure, but only Ray felt it when it wasn't falling.

Just as with the previous confession we follow with a rocker. A House in the Country blends a ramshackle Chuck Berry groove with the kind of hectoring vocal line that made Dedicated Follower of Fashion great and a relentless eye for detail that lifted the angry Well Respected Man above its peers. Here, it's funnier as the uppercrust brat who ascends to his position because his sherry-filled Old Man fell down the stairs and broke his neck. A series of bamming verses crunched together with Dave Davies' twenty-years-too-early new-waveish chugging chords, everything is kept in a party spirit. But Ray is not letting this undeserving goose off lightly. As everywhere around him the Carnabitian Army marches on, he's got even less of a connection between the joy of swinging London than the session man who at least gets close to the centre of the vibe.

Ray Davies didn't like the bright pyschedelic look of the cover art with its pink butterflies and fashionably moustachioed dandy, preferring something more subdued. The Kinks origins had included dressing up in hunting pink and playing rough edged R&B to the darling set. They carried a foppish image well up to the first hits and found it hard to shake. This could have flet as either a taunt or a clueless fit-up by the record company. While there seems to be a gulf between the content and the dayglo Chelsea images if you see latter in the spirit of the former it's far less a celebration than a sneering extension of some of the jibing, satire and outright anger driving this set.

The old Side Two begins with gushing surf. A Ventures style rhythm bounces up on the tom toms. The scratchy jangle of twin Davies guitars joins the shuffle. Dave breaks off to add mid range slides that sound more like the blues than Hawaii but that's the point. The narrator has won a Holiday in Wakiki and he jets all the way over the ocean to the big blue Pacific for a tan among the hula girls only to find that their grass skirts are made of PVC, the bamboo beach stalls are Coca Cola franchises, a genuine ukelele set him back a fortune and even the hula girls are New Yorkers of European descent. Everytime I hear this it reminds me of about half of the Brits I've met who have come to Australia for the fun in the sun, loaded up on Chinese made stuffed Koalas and boomerangs, and complain about everything being so DIY. You get a lot less of that these days but it always made me laugh. Ray recognised himself and managed to both whinge and own up to his naivete. And he gets to play with the language beautifully. It's justly recalled that Ray Davies could write a strong lyric about what he'd gone through but this gets close to the Edward Lear or Lewis Carroll he would have learned to read by:

A big brash riff starts up on the guitars but relaxes into an almost Latin afternoon groove for Most Exclusive Residence for Sale. This might be the sequel to story of the upper class twit in House in the Country but this is from another side of the Fab Britain in the '60s where any old kid could soar from dirt poor origins with a little verve and shove a common as muck accent into the ears of the establishment. This could be a David Bailey or a Mary Quant but it's one who didn't get that hard work was still needed to stay self made. He turns to the bottle and feels better until he sees the ad for the urban palace he has to sell to pay everyone off. It's a cautionary tale but there's a kind of solidarity in the lilt and the la-las at the end. maybe next time, mate, just don't throw it away again. There's a real thread here to the greatness that is to come on the storytelling albums of the late '60s like the following year's Something Else and the mighty and deathless Village Green in '68. If this bit of the album doesn't speak to you as much as the brighter tracks then walk on by, keep your voice down and don't knock. There are people living there.

Fancy begins with a delicate guitar figure blurring the line between a fourth and a major third when another comes in with a big whole tone string bend. This strange short number continues the work the band did on the compelling single See My Friends which established a distinctly Indian influence in British rock music that would hang around for the rest of the decade. This was months before George Harrison's very non-Indian use of the sitar on Norwegian Wood and Jeff Beck's splendid raga-like riff in Heartful of Soul. It might have helped that Ray Davies was not so much experimenting with the stuff of the mystic east but recalling hearing, for real, Indian fisherman chanting while at work on a tour stopover. Here, the sitars are almost defiantly left out again in favour of emulating the music with what the band knew, guitars. It makes for a compelling texture and its blend of mournfulness and meditation provide a comfortable bed for a musing about personal integrity and personal isolation which feels intentional and controlled. The drones continue as Ray's fragile voice grows strength and he hits the message. Is it trite, as he described psychedelia? Is it cod philosophy? To me it's in the voice that by the last two lines is full and assured, if describing a kind of gormless narcissism:

Then we're way back in deepest London for some music hall jazz and Ray is singing about a girl on the scene. Little Miss Queen of Darkness has all the allure of the swinging London bird on the town with her golden hair and false eyelashes. She's friendly and puts on a smile, drawing the lads wherever she walks. But he sees her sadness and how it freezes her from intimacy. The more dolled up and sociable she gets the more awkward she will be. Ray gives an explanation for this about the one big lost love but there's more to this, even musically. as the second chorus builds and the snare roll leads us into the dance in the middle we keep waiting for a solo that never comes. For 16 bars we are left in the middle of the dance floor with the girl whose movements might as well be lumbar exercises. The third verse saves us from embarrassment and tells us why she's a no go and won't ever be a go go. We could accept the jilted lover story but if we do we also have to accept that it left her a nervous wreck only able to appear to connect to the life around her but never able to touch it. We leave her dancing on and on.

The name and the musical treatment, the noodley doodley jazz shuffle with the brushes on the drums suggest a sneer but I think their lightness is eerie. This woman is in a vortex she might never escape. The love gone wrong tale might well have been the trigger. Of, course I'm speculating here but -- but since I am I'll go as far as to wonder if this is from something Davies heard about around the traps or is this one more self portrait, a gender-deflected confession or, more innocently, an astute description of another's distress. Though it starts that way Ray really isn't sneering at the frigid dolly bird, he's recognising trouble, her kindred trouble, dancing, dancing on.

A soul groove takes into Dave Davies' second lead vocal and an unambiguous love song. Some very nice tinkling from the Session Man and a pleasantly live vibe. You Look So Fine doesn't amount to much but doesn't try to. It fits perfectly in its place.

Then a strident almost military descent through a minor key lands with Ray lamenting his imagined lot as a rock star scoured by the taxman and abandoned by his trophy wife who has run back to her mother telling tales and taking everything he's got (which he rhymes, amusingly, with yacht). So he's going to sit back and get pissed on some ice cold beer and sing his blues. Sunny Afternoon is one of the most endearing of the Kinks mid '60s songs. It is musically pure with luscious acoustic guitar and falsetto harmonies that turn the crucial end phrases into small choral joys while the mock grimness of the situation marches on like time itself. A Kinks Klassic!

And then. I'm still surprised that the album doesn't end on the big single. There's just another one in the barrel here. Hang on, I'll get it now. I'll Remember starts with a catchy riff and launches into what now sounds like a previous phase of a band who have just spent over thirty minutes telling us that they've well and truly moved on. The clanging farewell is good natured, almost festive. A minor middle eight, a solo from Dave and one last chorus before a full stop. Done.

This is an album that breaks through disasters that might have prevented it and then even destroyed the band. But what a return from the ashes it is. There is more concept here then in albums by major players in the year to come as the twin threads of describing the grimmer side of the supposedly bright future that Britain was constantly telling everyone it already lived in and reports from the dark state this kind of observation facilitated. It is both a very personal statement and a full band effort.

The only aspect that mars the surface is the production. Shel Talmy bullshitted his way into becoming an independent producer at a time when few made that conceit work sustainably. Outside of the major labels and their stars like George Martin the choices for bands on wastepaper contracts at the low end of the food chain. Joe Meek beavered away, inventing as much as he recorded, handled his business less well but created real magic. And in the gap between this and the Joe Boyds to come was Shel, recorder of the Kinks, the Who and the Easybeats among others, the American in Blighty created some of the most persistently frustrating recordings of some of the strongest rock music of his era. As there are notable exceptions in the output (e.g. My Generation) I wonder how much of the teeth-grating tin tones he produced was down to difficulties with the bands themselves, including them insisting on bad paths and how much is just a blend of incompetence and cruddy studio facities.

Everyone got a little better for the next album (the great Something Else) but Ray is listed as co-producer and the pinnacle of the Kinks' '60s output Village Green is credited solely to Davies. It's a pity that whatever happened didn't happen a year earlier as even that level of improvement would have lifted this LP well beyond the state it comes to us now. It's Ray and the band and their songs that we hear but we must hear them through the clamour.

Still, the single that followed this album saw the band branching out with a brass section for the first time. Just like the Beatles but it wasn't Penny Lane it was Dead End Street. And that's one of the things I treasured about the Kinks as I foraged about for scant information on them as a teenager out of time in the '70s: the determination to look and keep looking.

Someone, I can't remember who, gave me a copy of the Nik Cohn/Guy Peellaert collaboration Rock Dreams in which Cohn's incisive observations were cast in bite size quotes against Peellaert's lavish fantasy paintings of rock stars from the '50s to the late '60s. And there, amid the pages of colour and glamour of swinging London with its rock royalty and paisley riches is the page for the Kinks. Ray Davies stands in a freezing, rained-on street with an imagined wife beside him who pushes a pram. A quote from Dead End Street is the only caption needed. Ray has an barely perceptible smile, staring back at us. I used to look at that page and a weird patriotism. Perhaps kinship is a better word but it went further. It felt like we were from the same country. Yeah, I know, that's the kind of crap that fandom doles out but that's a fandom I'd prescribe to any kid looking around.

Listening notes: I used the CD from the Kinks in Mono box set for this article. The sound quality is top notch but that also means it brings forward all the flaws and shortcomings of the production standards of the band's circumstances. Anyway, look for it.

With the British invasion the notion of rock groups who didn't also write their own songs was cast into antiquity. The Kinks, like the Beatles, Stones and everyone else, recorded their first LPs as their stage shows plus a few originals if you were lucky. Albums were singles extenders, higher priced platters of more of that sound in which the glamour shot cover art was about equally important as the tones on the grooves, product for purchase. The Beatles upped the ante in '64 when the Hard Day's Night album not only pushed their songwriting further but was composed entirely of Lennon McCartney originals. And then at the end of '65 produced Rubber Soul which threw down a gauntlet by not only being good but cohesive. It felt like a whole package, not just a group of songs. Face to Face is the first Kinks album of wholly original material. But it's more than that. While the R&B influenced rockers are still plentiful there's a lot more here.

We start off with an old telephone ring. A posh voice answers: "Yes, hellair whoo is thet speeeking pleeeese?" And BAM Party Line bursts forth. It's a Dave Davies number with a big shrill lisping yell and clanging guitars. It's about confusion and the words swing between trying to connect to someone else out there and the party lines that form during elections. Whether cobbled together or not it's a pretty indicative statement for the rest of the album in which brother Ray is going to lay his pysche bare and hone all those lashing attacks on the society around him. Confusion and anger you can dance to. Odd thing: the main verse melody of this song is identical to the song Connection on the Rolling Stones' Between the Buttons album from the year later. Don't recall anyone else pointing that out (though it might have happened at the time).

Rosie Won't You Please Come Home? begins with a descending progression through a minor key. Ray comes in with a plaintive high voiced melody, pleading for his sister to come back. This isn't a fictional character like Eleanor Rigby. Rosie was really his sister. Her departure for Australia in '64 had a profound effect on him. When he learned of it he ran to the seaside and screamed. Here he uses that to dive into the well of longing. She's not dead, just a long way away and no longer the reassuring hand on the shoulder or tales of fun in the West End or lessons in working the world. The rest of the family is there but he still feels alone with no one there to get what he is. The words are plain, often bathetically funny. She's never coming back because once things change they will never revert because when they do they feel fake and tokenistic. This is atypical for a rock band to come out with so early in an album but Ray was hinting at all sorts of things in those oddball numbers he'd throw in before like The World Keeps Going Round or See My Friends, strange melancholic daydreams. Even singles like Tired of Waiting have a heavy middle. Amid all the rave-ups like Till the End of the Day there was Ray, staring out the window lost in a rainy day.

Dandy starts with a chugging acoustic guitar and picks up with a Kinks trademark swagger. The young Lothario of the title runs around Swinging London like a stray tom cat on the make, hearing the stern warnings of friends and parents with equal disregard as he slinks around the windows and the backdoors winning and breaking hearts. He's one of the new youth of the 60s, uncrushed by national service and earning enough to keep his wild oats sowing as constantly as possible. He is fun and he is damage but, guess what, he's alright. I like the cover of this by Herman's Hermits a lot, it's fuller in production and the zingy middle eight has a real snarl to it. But it's also short of the acting that Davies gives it, he observes from only a few years' experience over his subject but it's enough to describe him perfectly and give a yell of support that mixes a supporting cheer with a croak of regret. His own days of dandyism are leaving and, like everyone approaching their mid twenties, thinks that his fifties might as well start in a few months.

A gorgeous acoustic guitar figure opens Too Much on my Mind. A loping bass below it swings up an octave (skillfully avoiding fret noise) and Ray comes in, taking us through what it feels like to have too many thoughts. His delivery is aching and reminds us of how strongly emotive his vocals are. Never is this more poignant than when he's on intimate ground. The middle eight of Set Me Free still sends shivers when I hear it breaking between self-annihilation and menace and it's as soft and quiet as the worst kind of resolve. Here, he sounds like he hasn't slept for days, forging out only the statements he knows to be true and none of them are pleasant. The song could easily be a wistful love gone wrong lament and no one would think the worse. But Davies uses this setting to talk about his breakdown. He isn't Syd Barrett, he doesn't go in and scream or record seventy takes of one part, he arranges his song to the last bar, oversees the performance and takes the mic in character. He's not in the pit when he does this but remembers it perfectly and the symptom he chooses is one that everyone who listens will know: insomnia. The strength it takes to front up to a microphone and play it vulnerable impresses here. Not melodramatic just drained, defeated, behind him the lilt of the beauty he knows he has created and which abandons him at his worst. But as the artist he is he waits and gets to work when he is once again able.

A bright harpsichord arpeggio bursts out and Ray's wry vocal comes in with the band telling us about one of the most important and unsung aspects of rock recording in the 60s, session players. The one in this song thinks very highly of himself, letting everyone know why they should think highly of him for what is really just doing the same job as anyone else minus the inspiration or feeling. He plays his notes and goes to the next job. Davies' taunting calypso inspired tune is thought to be a dig at Nicky Hopkins but I don't buy that. Not only is Hopkins playing on the track (that's his harpsichord, sounding pretty intentionally perfect and emotionally flat) but graced plenty of Kinks records thereafter as well as all but being the keys man on British records from the mid '60s to his death in the '90s, celebrated for both high skill, inventiveness as well as an egoless ability to fold in with the music as it was. Ray hinted that this song began by being about Hopkins and more recently Jimmy Page was thought to be the target (due to a fan-authored contraversy about who played the solos on early Kinks hits). But all this really has to be about is a session man, strolling from studio to concert hall, lending his grade five piano skills to advertising jingles and walloping rockers as London swang around him inventing its own fresh fun.

A thunderclap and ominous chord grinds on acoustic guitar and piano. As Ray comes in with a voice choking with dark awe as the summer day before him removes its mask to reveal the darkness that is always there underneath. Add a little rainwater and the hope sags, predators natural and supernatural emerge from the shadows and strike. If Too Much on My Mind was a calm recounting of an emotional extreme there is little in the way between the observer and his fear this time. Dave's guitar plays simple descents, plugged into the tremolo of his amp so that even the weaponry of rock music trembles with nerves. "Everybody felt the rain." Sure, but only Ray felt it when it wasn't falling.

Just as with the previous confession we follow with a rocker. A House in the Country blends a ramshackle Chuck Berry groove with the kind of hectoring vocal line that made Dedicated Follower of Fashion great and a relentless eye for detail that lifted the angry Well Respected Man above its peers. Here, it's funnier as the uppercrust brat who ascends to his position because his sherry-filled Old Man fell down the stairs and broke his neck. A series of bamming verses crunched together with Dave Davies' twenty-years-too-early new-waveish chugging chords, everything is kept in a party spirit. But Ray is not letting this undeserving goose off lightly. As everywhere around him the Carnabitian Army marches on, he's got even less of a connection between the joy of swinging London than the session man who at least gets close to the centre of the vibe.

Ray Davies didn't like the bright pyschedelic look of the cover art with its pink butterflies and fashionably moustachioed dandy, preferring something more subdued. The Kinks origins had included dressing up in hunting pink and playing rough edged R&B to the darling set. They carried a foppish image well up to the first hits and found it hard to shake. This could have flet as either a taunt or a clueless fit-up by the record company. While there seems to be a gulf between the content and the dayglo Chelsea images if you see latter in the spirit of the former it's far less a celebration than a sneering extension of some of the jibing, satire and outright anger driving this set.

The old Side Two begins with gushing surf. A Ventures style rhythm bounces up on the tom toms. The scratchy jangle of twin Davies guitars joins the shuffle. Dave breaks off to add mid range slides that sound more like the blues than Hawaii but that's the point. The narrator has won a Holiday in Wakiki and he jets all the way over the ocean to the big blue Pacific for a tan among the hula girls only to find that their grass skirts are made of PVC, the bamboo beach stalls are Coca Cola franchises, a genuine ukelele set him back a fortune and even the hula girls are New Yorkers of European descent. Everytime I hear this it reminds me of about half of the Brits I've met who have come to Australia for the fun in the sun, loaded up on Chinese made stuffed Koalas and boomerangs, and complain about everything being so DIY. You get a lot less of that these days but it always made me laugh. Ray recognised himself and managed to both whinge and own up to his naivete. And he gets to play with the language beautifully. It's justly recalled that Ray Davies could write a strong lyric about what he'd gone through but this gets close to the Edward Lear or Lewis Carroll he would have learned to read by:

It's a hooka hooka on the shiny briny on the way to Kona

And in a little shack they had a little sign that said Coca Cola

And even all the grass skirts were PVC

I'm just an English boy who won a holiday in Waikiki

A big brash riff starts up on the guitars but relaxes into an almost Latin afternoon groove for Most Exclusive Residence for Sale. This might be the sequel to story of the upper class twit in House in the Country but this is from another side of the Fab Britain in the '60s where any old kid could soar from dirt poor origins with a little verve and shove a common as muck accent into the ears of the establishment. This could be a David Bailey or a Mary Quant but it's one who didn't get that hard work was still needed to stay self made. He turns to the bottle and feels better until he sees the ad for the urban palace he has to sell to pay everyone off. It's a cautionary tale but there's a kind of solidarity in the lilt and the la-las at the end. maybe next time, mate, just don't throw it away again. There's a real thread here to the greatness that is to come on the storytelling albums of the late '60s like the following year's Something Else and the mighty and deathless Village Green in '68. If this bit of the album doesn't speak to you as much as the brighter tracks then walk on by, keep your voice down and don't knock. There are people living there.

Fancy begins with a delicate guitar figure blurring the line between a fourth and a major third when another comes in with a big whole tone string bend. This strange short number continues the work the band did on the compelling single See My Friends which established a distinctly Indian influence in British rock music that would hang around for the rest of the decade. This was months before George Harrison's very non-Indian use of the sitar on Norwegian Wood and Jeff Beck's splendid raga-like riff in Heartful of Soul. It might have helped that Ray Davies was not so much experimenting with the stuff of the mystic east but recalling hearing, for real, Indian fisherman chanting while at work on a tour stopover. Here, the sitars are almost defiantly left out again in favour of emulating the music with what the band knew, guitars. It makes for a compelling texture and its blend of mournfulness and meditation provide a comfortable bed for a musing about personal integrity and personal isolation which feels intentional and controlled. The drones continue as Ray's fragile voice grows strength and he hits the message. Is it trite, as he described psychedelia? Is it cod philosophy? To me it's in the voice that by the last two lines is full and assured, if describing a kind of gormless narcissism:

My love is like a ruby that no one can see,

Only my fancy, always.

No one can penetrate me,

They only see what's in their own fancy, always

Then we're way back in deepest London for some music hall jazz and Ray is singing about a girl on the scene. Little Miss Queen of Darkness has all the allure of the swinging London bird on the town with her golden hair and false eyelashes. She's friendly and puts on a smile, drawing the lads wherever she walks. But he sees her sadness and how it freezes her from intimacy. The more dolled up and sociable she gets the more awkward she will be. Ray gives an explanation for this about the one big lost love but there's more to this, even musically. as the second chorus builds and the snare roll leads us into the dance in the middle we keep waiting for a solo that never comes. For 16 bars we are left in the middle of the dance floor with the girl whose movements might as well be lumbar exercises. The third verse saves us from embarrassment and tells us why she's a no go and won't ever be a go go. We could accept the jilted lover story but if we do we also have to accept that it left her a nervous wreck only able to appear to connect to the life around her but never able to touch it. We leave her dancing on and on.

The name and the musical treatment, the noodley doodley jazz shuffle with the brushes on the drums suggest a sneer but I think their lightness is eerie. This woman is in a vortex she might never escape. The love gone wrong tale might well have been the trigger. Of, course I'm speculating here but -- but since I am I'll go as far as to wonder if this is from something Davies heard about around the traps or is this one more self portrait, a gender-deflected confession or, more innocently, an astute description of another's distress. Though it starts that way Ray really isn't sneering at the frigid dolly bird, he's recognising trouble, her kindred trouble, dancing, dancing on.

A soul groove takes into Dave Davies' second lead vocal and an unambiguous love song. Some very nice tinkling from the Session Man and a pleasantly live vibe. You Look So Fine doesn't amount to much but doesn't try to. It fits perfectly in its place.

Then a strident almost military descent through a minor key lands with Ray lamenting his imagined lot as a rock star scoured by the taxman and abandoned by his trophy wife who has run back to her mother telling tales and taking everything he's got (which he rhymes, amusingly, with yacht). So he's going to sit back and get pissed on some ice cold beer and sing his blues. Sunny Afternoon is one of the most endearing of the Kinks mid '60s songs. It is musically pure with luscious acoustic guitar and falsetto harmonies that turn the crucial end phrases into small choral joys while the mock grimness of the situation marches on like time itself. A Kinks Klassic!

And then. I'm still surprised that the album doesn't end on the big single. There's just another one in the barrel here. Hang on, I'll get it now. I'll Remember starts with a catchy riff and launches into what now sounds like a previous phase of a band who have just spent over thirty minutes telling us that they've well and truly moved on. The clanging farewell is good natured, almost festive. A minor middle eight, a solo from Dave and one last chorus before a full stop. Done.

This is an album that breaks through disasters that might have prevented it and then even destroyed the band. But what a return from the ashes it is. There is more concept here then in albums by major players in the year to come as the twin threads of describing the grimmer side of the supposedly bright future that Britain was constantly telling everyone it already lived in and reports from the dark state this kind of observation facilitated. It is both a very personal statement and a full band effort.

The only aspect that mars the surface is the production. Shel Talmy bullshitted his way into becoming an independent producer at a time when few made that conceit work sustainably. Outside of the major labels and their stars like George Martin the choices for bands on wastepaper contracts at the low end of the food chain. Joe Meek beavered away, inventing as much as he recorded, handled his business less well but created real magic. And in the gap between this and the Joe Boyds to come was Shel, recorder of the Kinks, the Who and the Easybeats among others, the American in Blighty created some of the most persistently frustrating recordings of some of the strongest rock music of his era. As there are notable exceptions in the output (e.g. My Generation) I wonder how much of the teeth-grating tin tones he produced was down to difficulties with the bands themselves, including them insisting on bad paths and how much is just a blend of incompetence and cruddy studio facities.

Everyone got a little better for the next album (the great Something Else) but Ray is listed as co-producer and the pinnacle of the Kinks' '60s output Village Green is credited solely to Davies. It's a pity that whatever happened didn't happen a year earlier as even that level of improvement would have lifted this LP well beyond the state it comes to us now. It's Ray and the band and their songs that we hear but we must hear them through the clamour.

Still, the single that followed this album saw the band branching out with a brass section for the first time. Just like the Beatles but it wasn't Penny Lane it was Dead End Street. And that's one of the things I treasured about the Kinks as I foraged about for scant information on them as a teenager out of time in the '70s: the determination to look and keep looking.

Someone, I can't remember who, gave me a copy of the Nik Cohn/Guy Peellaert collaboration Rock Dreams in which Cohn's incisive observations were cast in bite size quotes against Peellaert's lavish fantasy paintings of rock stars from the '50s to the late '60s. And there, amid the pages of colour and glamour of swinging London with its rock royalty and paisley riches is the page for the Kinks. Ray Davies stands in a freezing, rained-on street with an imagined wife beside him who pushes a pram. A quote from Dead End Street is the only caption needed. Ray has an barely perceptible smile, staring back at us. I used to look at that page and a weird patriotism. Perhaps kinship is a better word but it went further. It felt like we were from the same country. Yeah, I know, that's the kind of crap that fandom doles out but that's a fandom I'd prescribe to any kid looking around.

Listening notes: I used the CD from the Kinks in Mono box set for this article. The sound quality is top notch but that also means it brings forward all the flaws and shortcomings of the production standards of the band's circumstances. Anyway, look for it.

Sunday, October 23, 2016

1966 at 50: The Byrds' 5d Fifth Dimension

It was so hard to get to hear the Byrds in the mid-70s that it was through luck and nothing else that the only way I got to hear the Turn Turn Turn album was a cassette dubbed by a school friend from his sister's copy. The copy was an original mono LP from 1965. Even the compilations were hard to come by. At a time when even The Beatles were only available in their late period. If you wanted Rubber Soul you had to know someone who had it.

I read about Eight Miles High before I heard a bar of it. It was shrouded in contraversy because of the word high in the title. Even back in the 70s that seemed weird to me. I had to imagine what it sounded like. I did finally hear it once on the radio during a special called Twang about the role that electric guitars played in rock music. For three or so minutes my world stopped. I didn't think to set it up to tape it. When it was over it was gone forever. I tried reconstructing it from that memory but knew I only had the first few chords and opening line.

The 80s were much kinder to the legacy of 60s bands and after a few reissued compilations the original albums began appearing in record shops. Apart from anything else, a great many post punk musicians were turning to the best of the 60s rather than the immediate past for a kindred style. Among the reissues was the Byrds back catalogue but such was the record-buying decision tree of the cashless uni student, I figured I already had the singles compilation and there seemed so many covers on the original albums that I couldn't justify anything instead of a new Teardrop Explodes or Siouxsie spinner.

Then, later, after a year working at a local theatre I left to pursue writing a novel (nyerk nyerk) and received a kind of thank you payment which allowed a few records and more. I got the first three Byrds albums. So I finally heard this one. I'd heard already heard six of the tracks on compilations. Nevertheless, context is everything and this was their entry into the all important 1966 albums ranks. So, what's it like and does it still work?

The cover art is all 60s zeitgeist. The band variously kneel, sit or stand on a Persian rug against a background so black that it looks like the outer reaches of the Zorgon Galaxy. Each band member is holding a white disposable plastic cup with red liquid that could be cherry cordial or something more suitable for creating the impression that they are flying on a rug in the outer reaches of the Zorgon Galaxy. Above them the CBS logo, stereo logo and set list form a kind of arch around the album title in a blocky white font which floats above Byrds in huge paisley pattern letters. If you'd been in any danger of mistaking this for one of the series of Sing Along With Mitch Miller and the Gang from the 50s that danger was erased. So how does it sound?

5D starts without a riff or a snare hit, just a sudden fall into the big floating jangle and warm vocal singing of the expanse of the universe. Falling through the quantum dark somewhere between a folk rock workout and a country waltz, this hymn to the wonders of science catches us from the start as Roger McGuinn's folk club vocal is soon joined by the cut glass harmony of David Crosby's tenor. At one point McGuinn sings a vowel as high as he can go and as the chord changes Crosby comes in even higher with a a falsetto note as the highly compressed Rickenbacker 12 string snakes around with tentacles of pure chiming light. If anything was going to gently but firmly tell Byrds fans that they had moved on from Dylan covers this is it.

Wild Mountain Thyme hearkens back to the folk of the first two albums with a mix of chiming guitar and solemn choir from the valley earth. This time there's a string section that blows in like a cool breeze. It's a beautiful piece and you'll never skip it and, while it reminds us of the joys of the peaks of the previous albums, we've already heard the future and want more of that.

Mr Spaceman like the previous two tracks opens without a 12 string riff which makes a hat trick of departures from the first two LPs. Bam and you're into it. McGuinn sings a country-flavoured jig about a close encounter of the third kind. The bouncy 2/4 time and bright stacked harmonies suggest a jokey throwaway but the song's science fiction elements would return repeatedly in the band's output.