Andy's Chest rolls out gently like it's being made up on the spot. "If I could be anything in this world that flew, I would be a bat and come swooping after you." It's like a song for kids but by The Velvet Underground. A light electric guitar and bass plod along below. When the second verse starts the rest of the band come in and it reminds me of nothing so much as the backing track of almost anything from The Man Who Sold the World. Well, the band is almost the same and this is the point at which I need to introduce the producers of this record: David Bowie and Mick Ronson. Bowie was already an admirer of Reed, going back to the Velvets days and Mick had become Bowie's indispensable collaborator, shining through on a heavily individual electric guitar tone, courtesy his venerable Les Paul Custom, various distortion pedals and usually a big Marshall amp. Not only does the band sound like Bowie's, as soon as the baaaaaa baaaaaa ba ba ba ba ba baaaaa backing vocals come in, the sense that Reed is benefitting from the deluxe crest of session players and if there was anything you already liked about Bowie you will like about this record.

Perfect Day.An expanse of piano chords in a minor key but so expansive that it sounds warm rather than sad. A list of pain-killing activities of a loving couple are recounted from a life that sounds comfortable. The chorus swings into the major and everything just gets better. The phrase "you keep me hanging on" is not the complaint from the Motown song but a note of deep gratitude. Why? The second verse, sung in a more choked voice, says what Reed really means when the key line appears: " You made me forget myself. I thought I was someone else, someone good." He has been playing a fantasy to himself. All the Hallmark movie tones, the lingering phrasing that seems to taste the words as though they were the experiences themselves, are just masking the person he knows he is. After a gentle afternoon shower of instrumental drama we close on a coda, all but whispered and in the major: "you're going to reap just what you sow." It repeats until the soft conclusion shuts it down on a lonely figure who spent every last atom of good he ever had. This song is among those that get rolled out when an emotional occasion beckons, as wistfully joyous. I've played it at a wedding for the groom to sing and the guests around us joined in for the chorus. I kept my expression blank. (What's next, Love Will Tear Us Apart?) This remains one of Reed's finest moments where he wasn't shy of creating sincere beauty, even to the point of playing down its thorns.

Hangin' 'Round is a boogie with a glam rock mix of blues accents and 6th chord grind as Reed introduces a list of eccentric socialites whose quirks both amuse and bore Reed. Are they really still hanging around doing all those things?

Walk on the Wild Side starts and maintains a gentle shiuffle, Bowie style 12 string rhythmic strumming as the signature twin basses play the long looping hook. Reed is almost talking as he recounts the tales of local characters who transformed themselves in personal metamorphoses from their unsympathetic beginnings to a New York demi monde that welcomed them. These modern folk figures, all based on people Reed knew well from the scene around Andy Warhol are not just survivors but stars; they have come through ordeal and emerged in triumph. Reed sings quietly from the sidelines. The freaked out hedonism of Sister Ray and nightmarish world of Lady Godiva's Operation are distant recollections. Their best-revenge good living is celebrated here in one of Reed's most enduring statements. And, lest we forget, it's a ton of fun.

Make Up is a Velvets-reminiscent second person address with an odd mix of strummy electric guitar and tuba. Reed's portraying a crossdresser in matter of fact terms that might have felt adolescently provocative at the time but for the defiant chant of, "we're coming out."

Satellite of Love starts all at once, a piano-led ballad observes a sex magnet who gets around and just keeps going. Reed confessed this song to be about his own jealousy, watching from afar a figure whose power he could not claim and get away with it. If anything was Bowie-ish before this track this arrangement wipes the floor. The falsetto bom bom boms in the chorus and then the mighty wolf howl in the coda bring this close to being a Bowie song that Reed was guesting on.

Wagon Wheel starts with more of the glam rock but comes to a sudden stop so Lou can kneel in an empty church and confess to a painted wooden Jesus. Back on the wagon we keep up with the rockiness. Lou is zonked or just high on an occasion but he seems on the verge of collapse. But danger is just part of it all. He pleads for a hand to stop him rolling over and going before he's ready.

New York Telephone Conversation is a 2/4 piano vamp with electric bass. Gossip, night life, social life, what to wear and who to care? Bowie descants Reeds almost spoken vocal, sometimes in perfect pitch but when necessary more dissonant, whispering like wasps for the lines about scuttlebutt. It's zingy but it's fun.

I'm So Free is bright rock and roll with percussive backing vocals. The narrator is skipping along the pavement carefree, drugfree, responsibility-free and everything he's celebrating starts to sound like he got there through helping hands less sympathetic than the ones in Wagon Wheel but from richer bodies. Is he a prodigal hippy back in the fold? A reformed junkie? Wherever he's been all he seems to have learned is not to go there again but nothing of why or how he got there in the first place. It's not exactly denial but the zinger is that he will probably never live to regret the strain he gave to others. Mick Ronson's decidedly sour lead bends in the joyous coda provide a kind of witness to its shallow triumph.

Goodnight Ladies. Another tuba bomping on with a slow 2/4 from the days of jazz in the Big Easy. When we hit the verse a toodleydoo clarinet rises behind him like a last call at a bar. Soon enough we have a trumpet wailing along. It's the kind of lament of loneliness belied by the philosophical acceptance of the tone and the sweet beauty of the music that is made to be played live in bars filled with smoke and shots of rye. If we're paying attention as we smirk at the tv dinners or appointment with the late night news we might catch the quote from made Ophelia in Hamlet as she bids adieu to the court and makes her way to her suicide in the river. See ya.

By the time I heard this I was much more familiar with Bowie who seemed to be both historical and present. I knew he'd produced it and that it had come out the same year as Ziggy Stardust. Those facts were unremarkable when hearing the arrangements here but the portraits of the human marginalia here feel more intimate and lived than anything about moving like tigers on Vaseline. The thing that struck me first when I played it all the way through the first time was how much older Reed seemed than Bowie.

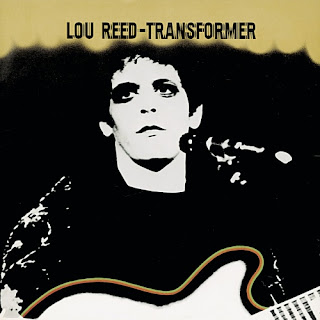

There were only five years (!) between them but Reed's experience weighed so much more heavily on his invention than Bowie's. Unlike the attempts at conventional and then whacky character-based pop that led to the 1967 debut under the Bowie name, Reed had already lived the material with his tribe that had informed the first Velvet Underground record and when the noise breaks out in Black Angel's Death Song and European Son they are already saying no to the honest world. When Transformer came along to be recorded Bowie bestowed Reed's archness and daggers with tinsel and grease, offering a blanket of brightest pop music to throw over the darkest of Reed's observations and the corrosion of his humour.

This was Lour Reed's second solo album. The first is self-titled. It's ok. There are some great songs like Ocean but there's a problem. It's been arranged and produced by thought trains that led to the singer songwriter end of the top forty, the Jackson Browns or Albert Hammonds. Whether it's a Stonesy groove (Walk it and Talk it even borrows and mortgages Keith Richards' riff from Brown Sugar). That was the day but this sounds less like its time that that of musicians who'd earned that kind of identikit rock to play for the balance of their careers. Bowie added fun so if the tone was camp it would have extra mince or if cinematic and tragic it could swell into a landscape of sound to make the hardest swoon. Bowie read Reed in a way that bypassed a hipster knowledge of the charts and what the adult oriented radio was playing and played the record right into where the kids lived.

From that experience, Reed never turned back. He'd already done much to break the mould of what rock bands should sound like and that first disc slotted him right back into the machine. You might have noticed the debut and nodded but you could love this album the way you loved White Light/White Heat and the teens who liked the snappy choruses and singalongs could love it, too. And it was still Lou Reed, the same Lou Reed who subverted the sombreness of Lady Godiva's Operation with intervening anti-pop interjections or took a side of an LP to describe a debauched party, but also a Lou Reed who stood up from the Rolling Stone photo shoot as a has been on page 20 and walked into the kind of stardom he could only fantasise about back in the bad days.

Transformer doesn't just describe the characters in these songs, it is a fanfare announcing a new career which Reed maintained credibly to the last. What are friends for, eh?

No comments:

Post a Comment