Afore I get into it I'm just going to point out that the track order I'm representing here is the original. The CD release changes the order and I'll be addressing that later but for now I'll be talking about the way I heard the record initially and for decades afterward.

From the silence there approaches what sounds like an old rustbucket car wheezing and creaking toward us. For All We Know is only synth pop in a technical sense (so to speak) but this track has no sense of automation. A bedrock of interlocking arpeggios that lean toward a kind of brass band from a Tom Baker Dr Who episode cranks up. It's the vocals that sound programmed. A sprightly melody sung in unison which separates out to lead and backing vocals for the chorus starts out so crisply that you suspect electronics but it really is just the singing of a very well disciplined band. As for the lyric, no strong idea and a mondegreen: do you control your thoughts, do you really have free will? And the chorus has always sounded like: "Haven't got a heart, haven't got a hope, haven't got a weirdo." Sorry, folks, but if you don't print them on the sleeve or allow them to be transcribed on the net we just have to guess.

And then it's quiet again just long enough for the sound of the notes from Popcorn falling gently from the sky as a low key droning vocal motif loops like a distant choir. Dave Mason enters with a melody as silky and melancholy as the first few bars, musing the blues on love and fame. And then comes that chorus: "I never wanted to be in Quasimodo's dream. Shall I beg the ringmaster please find another me?" That's not necessarily about being Quasimodo, of course, but just part of his dream. It could be about despite or low status, about a mass of horny men whose hearts were more monstrous than how they saw the old bell ringer. It might more simply be a yearning for peace after feeling the worst of attention. Whatever, it has pulled the song's teller down to the earth. After two spare verses the rest is atmosphere and quiet sadness that rolls into mesmerism. There's a beautiful and eerie video for this song. Greatness.

The bouncy, clean and bright According to My Heart springs to life after the fade of the title track. The band put what looked like a sticker (but it was just printed) that stated that the song was only on the album at the insistence of the record company on the inner sleeve. A few things to think about there. The inner sleeve on both sides is mostly a long list of acknowledgements and thank-yous ranging from people who helped the record get recorded and produced etc to puppets and favourite figures from history. The "sticker" is printed at an angle on both sides of the sleeve. If the record company had forced them to put the single on the album they also agreed to the disclaimer. If that's just a joke it's a lot of trouble to go to for such a slight one. Is it an arch means of drawing attention to the song (a cover version of an ol' country number)? The song itself doesn't seem to care. It just skips along at a canter and fades.

After the News bounces in with even brighter pings and tingles. Mason's spirited vocal asks us what we'll do after the news. We in the post-tv world might wonder what the particular news was but the darker and more immediate meaning here is about how we switched off after dinner and joined the transmission drone of prime time soaps and endless commercials. Or will we choose to emote, in whatever way suits? Will we jump in the air or quieten to a pallid silence? The news might be about war or a celebration. Will we at least engage with the tidings instead of deflate and plug in? Typical of this band this is served with a contradictory sheen so smiley that we are tempted to tap toes along with the beat and sing along as though it's Happy Birthday or a jingle for antacids.

In case we still have any breath after this Colourful Clothes zaps and buzzes to life with the energy of a skipping chant. The verse is all whydja go and break my heart with voices in unison. Then a pre-chorus bridge splits the voices into a dizzying harmony that tastes like it's made of sherbet powder. The chorus is the title phrase followed by some call and response whoa-whoas. Second verse same as the first but then a big raga rock line snakes up from below before an instrumental verse, that pre-chorus loopiness and the chanting chorus again, as before sounding like a lot less fun than the bouncing music. If you noticed the tv ads of the time or went to parties that looked like them, the neon rush of hair and fabric might have given you the bad kind of rush. That's what I heard here and still do. Then again, I bought out whole racks of op shops because the material was black.

Shout and Deliver continues the bells and chimes of the keyboard sounds but slows it down to sober as the minor key layers of vocals overlap in the minor. "Shout and deliver. Don't run away..." Be here, be loud, the future is yours to write. It's poignant that this was a single, something you might turn up when it came on Countdown. This band that called out to you to engage, not just with them but with everything around were keeping their message clear and insistent, not just slow-dancable. The vocal arrangements to this one border on Eastern Europe and in their own way remind us of the sparse and delicate beauty of the title track.

Side two changes things. The title track has already drowned in melancholy but Dubbo Go Go just takes us downward. Against an initial flurry of chimes an accent so broad that the two words it pronounces ("Australia calling") sound less motivated by humour than by fury. A large cranking machine of fuzzed guitar riffs, heavily off-accent rhythms that make it sound drunk and angry to the extent of paralysis. Over this comes Mason's bittersweet vocal describing his home town in terms that remind me of Peter Carey writing about the Bacchus Marsh of his childhood, with precision and naked chills. "YOu all it very saleable. I call it social dyssentry." And the chanting chorus with its modal fanfare melodics tells us to dance on our way out: "Dubbo go go go go ..." The longest and most depressing track on the album was done while the band were clearly on the rise to a creditable career and might have left the experience of the town as so much waste matter behind them. This is not a case of whingeing about coming from a small town, it sounds like a voodoo curse.

In complete contrast comes the trotting Smokey Dawson Show, atop the clopping synth percussion comes a lovely wordless vocal and electro trumpet tune that comes from a different part of medieval Europe than the chorus of Dubbo Go Go. I use to play this for a breezy little breather. Smokey Dawson was a bright mooded singing cowboy in Australia whose radio and tv appearances were designed to delight with anodyne thoughts and tunes and did. So does this. It's lovely.

Depression comes out of the shadows as a restless electro beat and chanting style vocal from a number of voices. The title is used both emotionally and economically as a future dystopia is evoked. Rather than anger that might be suggested by the violence of the rhythm there is a sadness to it as from a witness to horror who is powerless to intervene.

Rupert Murdoch is a naive electropop instrumental that was either named after as a joke or has an obscure connection with the media Goliath. A synth flute tweets over a thudding machine like throb. Then, in less than a minute and a half, it's over.

Kitchen Man is a sign of things to come. Almost completely synthesised, this Bacharach style plaintive ballad in which Mason's narrator in a voice that is both perfectly pitched and tired as hell sings of the length and labour of his days in a kind of role reversal. Is this a precursor of the men's movement whingeing as soon at the first point of redressed balance or is it a comment on it? The music and performance is genuinely moving and lyric so free of safe word winks that it's almost impossible to tell. My choice is for irony, that this is the lament of a man who is finally finding out about his wife's daily work and crying unfair. Mason plays it straight which only adds to the ceaseless beauty of the song's motion, melody and the inspired choice to use a fretless bass to stand in for a lower brass section that Bacharach might have used here. Beautiful and troubling as the best this band could offer.

Ohira Tour is a group chant that sounds like a commercial for the Japanese industrial leader with chunky pentatonic koto-like synths. It's three seconds short of a minute. Cancer crawls from the dark between tracks with varispeed spoken word (mostly the title) the same Bacarach fretless playing a theme before the amelodical chant of the title begins, surrounded by squeaks, squelches, shrieks and a host of electronic sounds. A speeded up voice spells the title word and then it fades, bringing the album to a strange close. The end of the story happens the way it seemed to be happening to every member of the population of the soon to be post-industrial world.

This was not declared to be a concept album at the time but you could be forgiven for thinking it was one. Mega money is scary, people on the ground suffer at its hands as they are corporatised, pushed into consumerist hives with canned culture. But while these themes are on clear show here this is not an electrobusker's protest set. The difference involves knowing a little about the time of its creation and those who created it.

Australia at the end of the '70s and the beginning of the '80s was a time of political stifling from above wherein a kind of Kingswood Country notion of an old Australia was still being peddled. The increasingly public influence of Japanese purchasing power was making the old ANZACs (real and imagined) restless and Murdoch media was starting to rule life on the planet. It was flight or go back to Dubbo and play covers at the local pub or try to change it one bored child at a time.

Band like Midnight Oil dealt with this by fashioning stadium-filling music with sloganeering choruses that were as catchy as Vegemite commercials. The Reels were not like them. More contrarian than counter culture, Mason and the crew had found a musical niche by which to bitch and didn't care if it sounded more personal than communal. When you consider how arch Ohira Tour is or difficult to read Kitchen Man what you are left with is how you get on with the sound of it all. And there's ther other thing; in the year of synth pop this synth heavy record does not line up with the likes of Visage or Ultravox, reframing the old pop formulae with different instruments, nor does it approach the sci-fi bleakness of early Human League, Gary Numan or John Foxx: The Reels simply do The Reels.

It took decades for this album to appear on CD. I don't know the story of this but it might well have had to do with the problems of getting very old magnetic Tape to play nice after a long time dormant (it takes baking ... in an oven). When it did appear ten years ago the sound quality was refreshingly high and the digi-pack appealing in that it resumed the original LP's idiosyncratic packaging. It also featured a completely different track order.

The rerelease begins with the title track and ends with Kitchen Man. All the media theme tracks are put together like a medley (though not crossfaded). Strangest of all, the track that caused the band to include a permanent sticker (really part of the inner sleeve design) remains on the album. No one thought to remove According to My Heart (or the "sticker"). A change of mind or intensified joke? History will decide, if Dave Mason doesn't do that at some point himself. That's what it will take.

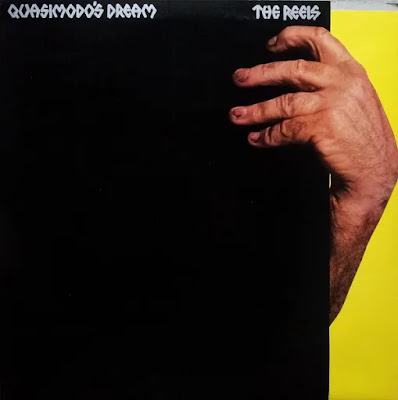

But all that means that this magnificent set of songs remains as vital as it did forty years ago and its intentionally eye fingering cover art is there to continue to annoy. Annoy it does and in the best way, this album offers its anger and pique set in music to delight, irritate or profoundly seduce. And surrounded by all this frenetic business is the song that will always make me ache for rainy Sunday mornings with dark shadows and glistening rain:

Shall I beg the ringmaster please find another me.

Oh I never wanted to be in Quasimodo's Dream.