Made from industrial strength disaster, Face to Face was the Kinks' strongest set to date. The band ended their 1965 tour of the US in disgrace with a ban that would keep them from maximised international success for years. The reason for the ban is obscure to this day but involved mismanagement and the constant internal violence that seemed to plague the band from the moment of their success. Songwriter in chief, Ray Davies, suffered a nervous breakdown in the months leading up to this set. He was entertaining the idea of doing a Brian Wilson and sending out a substitute singer to better handle the menacing confusion of adoration and hostility that playing to audiences meant. He just wanted to write his songs and play them with his mates. Well, it's more involved than that but that is in effect where he found himself at the beginning of 1966. And that is where he wrote, sang, played and oversaw the album Face to Face.

With the British invasion the notion of rock groups who didn't also write their own songs was cast into antiquity. The Kinks, like the Beatles, Stones and everyone else, recorded their first LPs as their stage shows plus a few originals if you were lucky. Albums were singles extenders, higher priced platters of more of that sound in which the glamour shot cover art was about equally important as the tones on the grooves, product for purchase. The Beatles upped the ante in '64 when the Hard Day's Night album not only pushed their songwriting further but was composed entirely of Lennon McCartney originals. And then at the end of '65 produced Rubber Soul which threw down a gauntlet by not only being good but cohesive. It felt like a whole package, not just a group of songs. Face to Face is the first Kinks album of wholly original material. But it's more than that. While the R&B influenced rockers are still plentiful there's a lot more here.

We start off with an old telephone ring. A posh voice answers: "Yes, hellair whoo is thet speeeking pleeeese?" And BAM Party Line bursts forth. It's a Dave Davies number with a big shrill lisping yell and clanging guitars. It's about confusion and the words swing between trying to connect to someone else out there and the party lines that form during elections. Whether cobbled together or not it's a pretty indicative statement for the rest of the album in which brother Ray is going to lay his pysche bare and hone all those lashing attacks on the society around him. Confusion and anger you can dance to. Odd thing: the main verse melody of this song is identical to the song Connection on the Rolling Stones' Between the Buttons album from the year later. Don't recall anyone else pointing that out (though it might have happened at the time).

Rosie Won't You Please Come Home? begins with a descending progression through a minor key. Ray comes in with a plaintive high voiced melody, pleading for his sister to come back. This isn't a fictional character like Eleanor Rigby. Rosie was really his sister. Her departure for Australia in '64 had a profound effect on him. When he learned of it he ran to the seaside and screamed. Here he uses that to dive into the well of longing. She's not dead, just a long way away and no longer the reassuring hand on the shoulder or tales of fun in the West End or lessons in working the world. The rest of the family is there but he still feels alone with no one there to get what he is. The words are plain, often bathetically funny. She's never coming back because once things change they will never revert because when they do they feel fake and tokenistic. This is atypical for a rock band to come out with so early in an album but Ray was hinting at all sorts of things in those oddball numbers he'd throw in before like The World Keeps Going Round or See My Friends, strange melancholic daydreams. Even singles like Tired of Waiting have a heavy middle. Amid all the rave-ups like Till the End of the Day there was Ray, staring out the window lost in a rainy day.

Dandy starts with a chugging acoustic guitar and picks up with a Kinks trademark swagger. The young Lothario of the title runs around Swinging London like a stray tom cat on the make, hearing the stern warnings of friends and parents with equal disregard as he slinks around the windows and the backdoors winning and breaking hearts. He's one of the new youth of the 60s, uncrushed by national service and earning enough to keep his wild oats sowing as constantly as possible. He is fun and he is damage but, guess what, he's alright. I like the cover of this by Herman's Hermits a lot, it's fuller in production and the zingy middle eight has a real snarl to it. But it's also short of the acting that Davies gives it, he observes from only a few years' experience over his subject but it's enough to describe him perfectly and give a yell of support that mixes a supporting cheer with a croak of regret. His own days of dandyism are leaving and, like everyone approaching their mid twenties, thinks that his fifties might as well start in a few months.

A gorgeous acoustic guitar figure opens Too Much on my Mind. A loping bass below it swings up an octave (skillfully avoiding fret noise) and Ray comes in, taking us through what it feels like to have too many thoughts. His delivery is aching and reminds us of how strongly emotive his vocals are. Never is this more poignant than when he's on intimate ground. The middle eight of Set Me Free still sends shivers when I hear it breaking between self-annihilation and menace and it's as soft and quiet as the worst kind of resolve. Here, he sounds like he hasn't slept for days, forging out only the statements he knows to be true and none of them are pleasant. The song could easily be a wistful love gone wrong lament and no one would think the worse. But Davies uses this setting to talk about his breakdown. He isn't Syd Barrett, he doesn't go in and scream or record seventy takes of one part, he arranges his song to the last bar, oversees the performance and takes the mic in character. He's not in the pit when he does this but remembers it perfectly and the symptom he chooses is one that everyone who listens will know: insomnia. The strength it takes to front up to a microphone and play it vulnerable impresses here. Not melodramatic just drained, defeated, behind him the lilt of the beauty he knows he has created and which abandons him at his worst. But as the artist he is he waits and gets to work when he is once again able.

A bright harpsichord arpeggio bursts out and Ray's wry vocal comes in with the band telling us about one of the most important and unsung aspects of rock recording in the 60s, session players. The one in this song thinks very highly of himself, letting everyone know why they should think highly of him for what is really just doing the same job as anyone else minus the inspiration or feeling. He plays his notes and goes to the next job. Davies' taunting calypso inspired tune is thought to be a dig at Nicky Hopkins but I don't buy that. Not only is Hopkins playing on the track (that's his harpsichord, sounding pretty intentionally perfect and emotionally flat) but graced plenty of Kinks records thereafter as well as all but being the keys man on British records from the mid '60s to his death in the '90s, celebrated for both high skill, inventiveness as well as an egoless ability to fold in with the music as it was. Ray hinted that this song began by being about Hopkins and more recently Jimmy Page was thought to be the target (due to a fan-authored contraversy about who played the solos on early Kinks hits). But all this really has to be about is a session man, strolling from studio to concert hall, lending his grade five piano skills to advertising jingles and walloping rockers as London swang around him inventing its own fresh fun.

A thunderclap and ominous chord grinds on acoustic guitar and piano. As Ray comes in with a voice choking with dark awe as the summer day before him removes its mask to reveal the darkness that is always there underneath. Add a little rainwater and the hope sags, predators natural and supernatural emerge from the shadows and strike. If Too Much on My Mind was a calm recounting of an emotional extreme there is little in the way between the observer and his fear this time. Dave's guitar plays simple descents, plugged into the tremolo of his amp so that even the weaponry of rock music trembles with nerves. "Everybody felt the rain." Sure, but only Ray felt it when it wasn't falling.

Just as with the previous confession we follow with a rocker. A House in the Country blends a ramshackle Chuck Berry groove with the kind of hectoring vocal line that made Dedicated Follower of Fashion great and a relentless eye for detail that lifted the angry Well Respected Man above its peers. Here, it's funnier as the uppercrust brat who ascends to his position because his sherry-filled Old Man fell down the stairs and broke his neck. A series of bamming verses crunched together with Dave Davies' twenty-years-too-early new-waveish chugging chords, everything is kept in a party spirit. But Ray is not letting this undeserving goose off lightly. As everywhere around him the Carnabitian Army marches on, he's got even less of a connection between the joy of swinging London than the session man who at least gets close to the centre of the vibe.

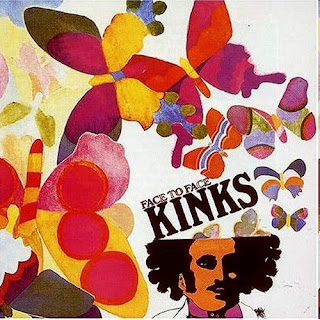

Ray Davies didn't like the bright pyschedelic look of the cover art with its pink butterflies and fashionably moustachioed dandy, preferring something more subdued. The Kinks origins had included dressing up in hunting pink and playing rough edged R&B to the darling set. They carried a foppish image well up to the first hits and found it hard to shake. This could have flet as either a taunt or a clueless fit-up by the record company. While there seems to be a gulf between the content and the dayglo Chelsea images if you see latter in the spirit of the former it's far less a celebration than a sneering extension of some of the jibing, satire and outright anger driving this set.

The old Side Two begins with gushing surf. A Ventures style rhythm bounces up on the tom toms. The scratchy jangle of twin Davies guitars joins the shuffle. Dave breaks off to add mid range slides that sound more like the blues than Hawaii but that's the point. The narrator has won a Holiday in Wakiki and he jets all the way over the ocean to the big blue Pacific for a tan among the hula girls only to find that their grass skirts are made of PVC, the bamboo beach stalls are Coca Cola franchises, a genuine ukelele set him back a fortune and even the hula girls are New Yorkers of European descent. Everytime I hear this it reminds me of about half of the Brits I've met who have come to Australia for the fun in the sun, loaded up on Chinese made stuffed Koalas and boomerangs, and complain about everything being so DIY. You get a lot less of that these days but it always made me laugh. Ray recognised himself and managed to both whinge and own up to his naivete. And he gets to play with the language beautifully. It's justly recalled that Ray Davies could write a strong lyric about what he'd gone through but this gets close to the Edward Lear or Lewis Carroll he would have learned to read by:

It's a hooka hooka on the shiny briny on the way to Kona

And in a little shack they had a little sign that said Coca Cola

And even all the grass skirts were PVC

I'm just an English boy who won a holiday in Waikiki

A big brash riff starts up on the guitars but relaxes into an almost Latin afternoon groove for Most Exclusive Residence for Sale. This might be the sequel to story of the upper class twit in House in the Country but this is from another side of the Fab Britain in the '60s where any old kid could soar from dirt poor origins with a little verve and shove a common as muck accent into the ears of the establishment. This could be a David Bailey or a Mary Quant but it's one who didn't get that hard work was still needed to stay self made. He turns to the bottle and feels better until he sees the ad for the urban palace he has to sell to pay everyone off. It's a cautionary tale but there's a kind of solidarity in the lilt and the la-las at the end. maybe next time, mate, just don't throw it away again. There's a real thread here to the greatness that is to come on the storytelling albums of the late '60s like the following year's Something Else and the mighty and deathless Village Green in '68. If this bit of the album doesn't speak to you as much as the brighter tracks then walk on by, keep your voice down and don't knock. There are people living there.

Fancy begins with a delicate guitar figure blurring the line between a fourth and a major third when another comes in with a big whole tone string bend. This strange short number continues the work the band did on the compelling single See My Friends which established a distinctly Indian influence in British rock music that would hang around for the rest of the decade. This was months before George Harrison's very non-Indian use of the sitar on Norwegian Wood and Jeff Beck's splendid raga-like riff in Heartful of Soul. It might have helped that Ray Davies was not so much experimenting with the stuff of the mystic east but recalling hearing, for real, Indian fisherman chanting while at work on a tour stopover. Here, the sitars are almost defiantly left out again in favour of emulating the music with what the band knew, guitars. It makes for a compelling texture and its blend of mournfulness and meditation provide a comfortable bed for a musing about personal integrity and personal isolation which feels intentional and controlled. The drones continue as Ray's fragile voice grows strength and he hits the message. Is it trite, as he described psychedelia? Is it cod philosophy? To me it's in the voice that by the last two lines is full and assured, if describing a kind of gormless narcissism:

My love is like a ruby that no one can see,

Only my fancy, always.

No one can penetrate me,

They only see what's in their own fancy, always

Then we're way back in deepest London for some music hall jazz and Ray is singing about a girl on the scene. Little Miss Queen of Darkness has all the allure of the swinging London bird on the town with her golden hair and false eyelashes. She's friendly and puts on a smile, drawing the lads wherever she walks. But he sees her sadness and how it freezes her from intimacy. The more dolled up and sociable she gets the more awkward she will be. Ray gives an explanation for this about the one big lost love but there's more to this, even musically. as the second chorus builds and the snare roll leads us into the dance in the middle we keep waiting for a solo that never comes. For 16 bars we are left in the middle of the dance floor with the girl whose movements might as well be lumbar exercises. The third verse saves us from embarrassment and tells us why she's a no go and won't ever be a go go. We could accept the jilted lover story but if we do we also have to accept that it left her a nervous wreck only able to appear to connect to the life around her but never able to touch it. We leave her dancing on and on.

The name and the musical treatment, the noodley doodley jazz shuffle with the brushes on the drums suggest a sneer but I think their lightness is eerie. This woman is in a vortex she might never escape. The love gone wrong tale might well have been the trigger. Of, course I'm speculating here but -- but since I am I'll go as far as to wonder if this is from something Davies heard about around the traps or is this one more self portrait, a gender-deflected confession or, more innocently, an astute description of another's distress. Though it starts that way Ray really isn't sneering at the frigid dolly bird, he's recognising trouble, her kindred trouble, dancing, dancing on.

A soul groove takes into Dave Davies' second lead vocal and an unambiguous love song. Some very nice tinkling from the Session Man and a pleasantly live vibe. You Look So Fine doesn't amount to much but doesn't try to. It fits perfectly in its place.

Then a strident almost military descent through a minor key lands with Ray lamenting his imagined lot as a rock star scoured by the taxman and abandoned by his trophy wife who has run back to her mother telling tales and taking everything he's got (which he rhymes, amusingly, with yacht). So he's going to sit back and get pissed on some ice cold beer and sing his blues. Sunny Afternoon is one of the most endearing of the Kinks mid '60s songs. It is musically pure with luscious acoustic guitar and falsetto harmonies that turn the crucial end phrases into small choral joys while the mock grimness of the situation marches on like time itself. A Kinks Klassic!

And then. I'm still surprised that the album doesn't end on the big single. There's just another one in the barrel here. Hang on, I'll get it now. I'll Remember starts with a catchy riff and launches into what now sounds like a previous phase of a band who have just spent over thirty minutes telling us that they've well and truly moved on. The clanging farewell is good natured, almost festive. A minor middle eight, a solo from Dave and one last chorus before a full stop. Done.

This is an album that breaks through disasters that might have prevented it and then even destroyed the band. But what a return from the ashes it is. There is more concept here then in albums by major players in the year to come as the twin threads of describing the grimmer side of the supposedly bright future that Britain was constantly telling everyone it already lived in and reports from the dark state this kind of observation facilitated. It is both a very personal statement and a full band effort.

The only aspect that mars the surface is the production. Shel Talmy bullshitted his way into becoming an independent producer at a time when few made that conceit work sustainably. Outside of the major labels and their stars like George Martin the choices for bands on wastepaper contracts at the low end of the food chain. Joe Meek beavered away, inventing as much as he recorded, handled his business less well but created real magic. And in the gap between this and the Joe Boyds to come was Shel, recorder of the Kinks, the Who and the Easybeats among others, the American in Blighty created some of the most persistently frustrating recordings of some of the strongest rock music of his era. As there are notable exceptions in the output (e.g. My Generation) I wonder how much of the teeth-grating tin tones he produced was down to difficulties with the bands themselves, including them insisting on bad paths and how much is just a blend of incompetence and cruddy studio facities.

Everyone got a little better for the next album (the great Something Else) but Ray is listed as co-producer and the pinnacle of the Kinks' '60s output Village Green is credited solely to Davies. It's a pity that whatever happened didn't happen a year earlier as even that level of improvement would have lifted this LP well beyond the state it comes to us now. It's Ray and the band and their songs that we hear but we must hear them through the clamour.

Still, the single that followed this album saw the band branching out with a brass section for the first time. Just like the Beatles but it wasn't Penny Lane it was Dead End Street. And that's one of the things I treasured about the Kinks as I foraged about for scant information on them as a teenager out of time in the '70s: the determination to look and keep looking.

Someone, I can't remember who, gave me a copy of the Nik Cohn/Guy Peellaert collaboration Rock Dreams in which Cohn's incisive observations were cast in bite size quotes against Peellaert's lavish fantasy paintings of rock stars from the '50s to the late '60s. And there, amid the pages of colour and glamour of swinging London with its rock royalty and paisley riches is the page for the Kinks. Ray Davies stands in a freezing, rained-on street with an imagined wife beside him who pushes a pram. A quote from Dead End Street is the only caption needed. Ray has an barely perceptible smile, staring back at us. I used to look at that page and a weird patriotism. Perhaps kinship is a better word but it went further. It felt like we were from the same country. Yeah, I know, that's the kind of crap that fandom doles out but that's a fandom I'd prescribe to any kid looking around.

Listening notes: I used the CD from the Kinks in Mono box set for this article. The sound quality is top notch but that also means it brings forward all the flaws and shortcomings of the production standards of the band's circumstances. Anyway, look for it.